Jeanette’s Feast

By Michelle Ann King

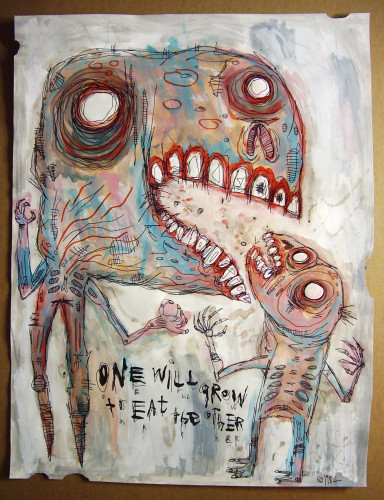

Illustration by Justin Aerni

Gavin loved weddings. He loved the occasion itself — the dressing up, the rituals, the dancing and drinking — but what he loved most of all was the sense of optimism. Marriage was a celebration of confidence — of believing that you’d made the right choice.

Gavin had never been married. He’d never had that kind of confidence, either.

No. That wasn’t true. For a little while, he had. When Jeanette was born, when he’d held her and let her put his finger in her mouth, he’d felt it. He’d closed his eyes and believed, in that single wonderful moment, that he could have all of it: the wedding, the honeymoon, the babies, the warm and welcoming home, the bliss of a huge, loving family.

But then his mother had taken the baby away, telling him he was holding her wrong, and when he went back to Fern’s room with a mug of hot chocolate, a bunch of roses, and a velvet ring box in his pocket, she was gone. Discharged herself, they said. From the hospital, and from his life.

But this wasn’t the time for melancholy memories, was it? No. It was time for congratulations and happiness. Cousin Cecilia was getting married, and that was something they should all be happy about.

Gavin picked up his champagne glass and raised it high. ‘To marriage and family.’

He waited, but nobody at the table echoed it. His young niece and her boyfriend were both tapping away at their mobile phones, and Uncle Frank was reading a newspaper.

Maybe they hadn’t heard him over the sound of the music. Gavin cleared his throat and tried again, but his mother grabbed his wrist from behind, jerking the glass and spilling its contents.

‘That girl,’ Moira said, the words gritting out from between clenched teeth, ‘is causing a scene. Get over there and sort it out. Now.’

Gavin gave a forlorn glance at the champagne soaking into the pink tablecloth. ‘What?’

Her hand tightened around his wrist until he felt bones grind. ‘I said now, Gavin.’

She bent down and put her mouth close enough to his ear that he could feel her breath, hot on his skin. ‘This is what you get, for constantly spoiling her. She’s not a child anymore, Gavin, she should know how to behave. I’m telling you now, if she embarrasses me in public one more time, she will regret it. And so will you.’

She let go of his wrist and Gavin jumped to his feet. He followed her glare to the back of the hall, where the buffet had been laid out on long tables. A large group had gathered around one at the end, and more people at the edge of the dance floor were turning to look.

He pushed his way through the crowd, Moira’s anger still beating down on the back of his neck. It was his own fault. He should have been watching Jeanette. Making sure she had something to do, something else to think about.

‘Excuse me,’ he said. ‘Sorry, excuse me. If I could just…?’

People moved aside reluctantly to let him through. At the front, they’d formed a semicircle around the buffet table. Around Jeanette. Everybody seemed to have their hands up, holding cameras or mobile phones. A sea of red lights flashed and winked.

‘Mind out, mate, you’re in the way,’ said a woman at his elbow. She was filming on an iPhone.

‘Sorry,’ Gavin said automatically.

‘Wow,’ the woman said, shaking her head. She sounded amazed, disbelieving and faintly envious all at the same time. ‘That kid can really put it away. I don’t think she’s even stopped for breath.’

The table had been laid with desserts. Gavin had seen it on the way in; a huge glass bowl of profiteroles, three-tier stands of frosted cupcakes, and at least five plates holding enormous cheesecakes, Victoria sponges, and strawberry gateaux. Now, the bowl, the cupcake stands and all but one of the plates held nothing but splodges of cream and a few crumbs. On the last plate was a six-inch-high chocolate fudge cake. While he watched, Jeanette cut a large slice and swallowed it in two bites.

‘Wonder if she’s one of those, you know, competitive eaters?’ the woman with the iPhone said. ‘Like you see on the telly. People who eat fifty boiled eggs in five minutes, that sort of thing.’

‘No,’ Gavin said. ‘She’s not.’ He stepped forward and took hold of his daughter’s forearm. ‘Jeanette,’ he said softly. ‘Come on. That’s enough, now.’

She looked at him with wide, glazed eyes. ‘You said I could have cake.’

From behind them came a muffled snort.

‘A slice,’ Gavin said, helplessly. ‘You have a slice of cake, Jen, not the whole thing.’

‘I was hungry,’ she said, and picked up the cake knife again.

The laughter was louder this time, with no attempt at muffling.

Gavin increased the pressure on her arm. ‘Put that down, Jeanette. Now come on, we’re leaving.’

She didn’t respond, but when he took the knife and plate out of her hands she didn’t resist, either. He turned her around, towards the exit.

‘Excuse us,’ he said, heat burning his cheeks.

The crowd eventually parted for them, but he could still hear the clicks and whirrs — and giggles — as he steered Jeanette away.

Moira stood by the door, holding her coat and handbag. Her head was high, her smile rigid. A muscle in her jaw twitched in an irregular rhythm.

‘I’ve ordered a taxi,’ she said. ‘I’ll go and lie to my sister about what a wonderful time we’ve had. You take that—’ she flapped a hand at Jeanette, ‘that disgusting creature outside and wait there.’

‘Mum—’ he said, but she’d already stalked away.

Gavin pushed the double doors open and shepherded Jeanette outside. ‘Do you want my jacket?’ he asked, but she shook her head. Even though her arms were bare in the sleeveless dress, she didn’t seem to feel the cold.

Which was just as well, since he wasn’t sure his jacket would actually fit her. At thirteen, Jeanette was already two inches taller than Gavin’s five foot eight. She wasn’t fat, not exactly, but she was definitely… large. The normal reassurances — excuses? — about puppy fat and big bones had provided comfort for a while, but were starting to lose their power. People used to watch her eat with indulgent smiles and approving commentary about good girls who cleaned their plates. These days, the smiles were getting nervous and the commentary usually ended up on the subject of type 2 diabetes and the obesity crisis.

Gavin shivered and pulled his jacket closed. The doctors said she was perfectly healthy, so what was he supposed to do? He wanted to be a good father. He wanted Jeanette to be happy. But maybe Moira was right. Maybe those two goals were incompatible. Maybe he didn’t know what he was doing. Maybe he never had.

He sighed. ‘Why do you do it, Jen? Why do you eat so much?’

She lifted her head and looked at him. In the sickly light of the streetlamp her eyes looked almost yellow.

She shrugged. ‘It’s what I’m good at.’

‘Have you seen this?’ Moira said. She was sitting at the kitchen table with a mug of coffee, untouched, by the side of her laptop. She swung the machine around so that Gavin could see the screen, which was showing a YouTube video.

It was of Jeanette, at the wedding. The camera panned along the devastated buffet table to Jeanette, who stood staring straight into the lens and chewing. At 32 seconds, she picked up a raspberry cheesecake the size of a pizza. At 58 seconds, it was gone.

In the background, Abba’s ‘Dancing Queen’ was playing. An awed voice could be heard over the top of it, saying, ‘Fuck me.’

The video had 734,823 hits.

‘Ah,’ he said.

‘This,’ Moira said, ‘is unacceptable. You need to do something about that girl. Get her seen to.’

‘But Mum, you know Dr Revin said—’

‘I don’t care what that old fool said. There’s something wrong with her.’

‘But—’

‘Are you telling me this is normal behaviour, Gavin? Are you?’

‘Well, I—’

She slammed the laptop lid shut. ‘I’m not going to be turned into a laughing stock by that freak. So I expect you to do something about this.’

‘She’s not a freak, Mum. She’s your granddaughter.’

‘Much as I wish it wasn’t the case, those two terms aren’t mutually exclusive. And if you’d done what I told you to do thirteen years ago, we would never have been in this position in the first place.’

If he’d given Jeanette up. Had her adopted. But he couldn’t. She was his. Maybe the only thing that ever truly had been.

Moira sniffed. ‘Clearly, that little tart knew what she was doing when she left that child behind. A mother knows when something isn’t right, trust me on that one. Not that she was what you’d call normal, either.’

‘Don’t,’ he said. ‘Don’t talk like that.’

Moira ignored him, acted as if he hadn’t said anything. Maybe he hadn’t.

‘This is completely out of control, Gavin. Do you think food comes free? Do you think the supermarkets just give it away?’

‘No, but — Mum, I pay for Jeanette’s—’

She waved a hand. ‘But if you weren’t spending so much on her then you’d be able to pay me proper rent, wouldn’t you? I swear, it would cost less to keep a horse. And at least you could get some use out of it.’

‘Mum—’

She pushed her cold coffee away. ‘I told you to sort this out, Gavin. I expect you to teach that girl to eat properly. Like a young lady, not some kind of ravening animal. The only time I want to see her with something in her mouth is at the table, eating a normal meal at a normal meal time. Not constantly stuffing her face with whatever she can get her hands on. It’s disgusting, and I won’t stand for it any longer. Not in my house.’

‘But I— She—’

‘For God’s sake. You’re her father. Act like it. Or you can take her to the zoo where she belongs. I won’t have my home turned into some kind of freakshow, so you can either sort this out or you can leave, the pair of you. Do you understand me?’

Gavin looked down. ‘Yes, Mum.’

She smiled. ‘Good boy.’

Jeanette came in and went to the cupboard. She took out a family packet of Wotsits and ripped it open with her teeth. She plunged her hand inside.

‘What’s for breakfast?’ she said, still chewing. Orange crumbs dropped from her lips.

Moira shuddered and pushed her chair back from the table. ‘You’ve got two weeks,’ she said, and walked out.

Gavin checked his bank account. He never spent a lot, but then he didn’t earn a lot, either. Library Assistant wasn’t exactly a high-paying career. His mother was right: after he’d bought the weekly groceries, there wasn’t much left. Certainly not enough to rent somewhere to live in London. Or anywhere else, for that matter.

And it wasn’t as if what Moira wanted was that unreasonable, was it? A family sitting down to eat a nice dinner together, what could be wrong with that?

It was one thing when you were a child, thinking that the world was a wonderful place where you could do what you liked, but Jeanette was growing up and it was time she learned about reality. It couldn’t possibly do her any harm, to learn restraint. Self-control. It would be good for her. That was what parents did — they made sure their children learned what they needed to know.

It was his duty, as her father, to teach her.

But he didn’t know how. It wasn’t as if he hadn’t tried to talk to her. He’d explained about nutrition and good dietary choices. He’d explained about money management and living within a budget. He’d explained about etiquette and social niceties.

Jeanette had listened to his speech with apparent attention, nodded and answered his questions with every indication of understanding. Then she’d gone to the fridge, taken out a packet of bacon and eaten it raw.

There had to be something she didn’t like. Something she wouldn’t eat. Didn’t there?

On Monday he left out cold pizza for breakfast, and put a marmite and honey sandwich in her packed lunch. Jeanette brought her plate and her lunch box back empty.

On Tuesday he tried sandwiches made with peanut butter, tabasco and pickled onion, with the same result.

Wednesday’s dinner of gorgonzola, anchovy and mango omelette was eaten without complaint, and when he made an ice-cream sundae on Thursday with alternating layers of minced garlic and sardines in barbecue sauce, she licked the bowl and asked for seconds.

On Friday, while blending soup made from oysters, Brussels sprouts, tripe and Scotch bonnet chillies, he had to stop and lie down. Jeanette finished it off for him, and ate the whole pot.

On the weekend, after doing some research online, he took the tube to a specialist shop in Kensington. There were lines, there had to be. Even for Jeanette. And surely, surely, this would be an uncrossable one.

He just needed to get her to say no, that was the thing. No, I won’t eat that.

‘These are a good choice for a first insect,’ the young assistant said. ‘For your daughter, you said, yeah?’

‘Um, yes. More or less, anyway, I—’

‘She’ll love them, don’t you worry. Now, you’ll be wanting the tank, the cork bark and the heating mat, then, yeah? Remember, these fellas are from a nice warm island, so you’ll need to keep the thermostat at about 18 to 25 degrees at the soil level. They’re not too fussed about humidity, a quick pass with a plant sprayer once a day should do the trick. And they don’t like it too bright, so watch that. The tank’ll stay fresh for quite a while, but you should clean it out every two to three months or so.’

‘I see,’ Gavin said. ‘Right.’

She gave him a reassuring smile. ‘Don’t worry, all this stuff is on the fact sheet. I’ll pop one in here for you.’ She began to box up his purchases. ‘They’re called Bert and Ernie.’

‘I— excuse me? What?’

The girl nodded at the cockroaches. They had black head parts, striped, shiny brown bodies and fuzzy-looking legs. ‘Bert and Ernie, that’s we called them. Bert’s the big one. Although of course, you don’t have to stick with that if you don’t want to. Most people rename pets once they get them home. But I think it suits them, don’t you?’

‘Ah,’ Gavin said. ‘Right. Pets, yes. That’s very… yes.’ He handed over his credit card.

When he got home, he set up the voluminous plastic tank in the shed, set up the heating mat and layered it with the bedding and bark chips. He added some of the special Cockroach Chow the assistant had recommended, and a milk bottle top as a water dish.

He sank down onto a mildewed garden chair and watched through the clear walls as Bert waved a feeler at him.

‘They’re cute,’ Jeanette said from behind him, and he jumped. ‘Can I hold one?’ she asked, turning her hand palm upwards.

‘I— well, I—’

She reached into the tank, picked up Bert and placed him on her palm. She lifted him up and brought him closer to her face. To her mouth.

Gavin chest constricted. But no. She wouldn’t. She couldn’t. Could she?

Bert scrabbled on her palm as she cupped her fingers. Her lips parted, revealing teeth that seemed very white in the dingy light of the shed.

‘No,’ Gavin yelled. He leapt to his feet, the chair toppling over behind him, and gripped Jeanette’s wrist. She blinked at him, her mouth still open.

He pulled on her wrist — gently at first, then with increasing force. ‘Okay,’ he said, ‘that’s enough for now. We don’t want to tire them out, do we?’

Jeanette looked reluctant, but she allowed the cockroach to slide off her hand and back into the tank.

Gavin replaced the lid and leant on it. He puffed out the remaining air trapped in his lungs and let his shoulders sag until his forehead rested on the glass. The coolness felt soothing against his overheated skin.

‘Are you all right, Dad?’ Jeanette said, but he just closed his eyes.

On Sunday night, Moira looked first in the empty cupboards and then the empty fridge.

‘I, er, I’ll ring for a pizza?’ Gavin said. He slid his hand around the back of his neck, trying to knead away the tension in the muscles. His fingertips dug in deep, but created no relief.

‘One week,’ Moira said. ‘One week, Gavin.’

He nodded quickly, then winced as the movement sent a flare of pain through his aching head. ‘Right,’ he said.

He made a peach crumble with half a packet of laxative powder. He baked a loaf of bread with the contents of the hoover bag mixed in. He made hot chocolate with a splash of washing up liquid. And finally, a casserole of dog food, bleach and motor oil.

Jeanette ate everything he put in front of her, said it was good, and asked for more.

Gavin was the one who found himself, when it eventually hit him what he’d done, kneeling in the bathroom and spitting bile into the toilet bowl. When his stomach felt as empty and wrung-out as the rest of him, he went into the kitchen and finished the washing-up. Then he sat down, put his head in his hands and cried.

Moira found him there two hours later and looked down at him with disgust. ‘Start packing,’ she said.

‘Some people shouldn’t breed,’ Fern had said to him, in the hospital.

He’d been shocked, then, that she could say such a thing. But now, he thought maybe he understood.

He wasn’t a good parent. He knew that now. But maybe… maybe he wasn’t the only one.

What kind of mother would turn her own family out on the street? Moira knew they had nowhere else to go. Would she rather see them living rough? Cold, heartbroken, starving?

Yes. Yes, he really thought she would. She’d leave her own son to die in poverty, and all because a teenage girl liked her food. That wasn’t a crime, was it?

So he had to ask himself, what kind of a woman could do something like that? And the only answer he could come up with was: an evil one. Someone who probably wasn’t a woman at all, but some kind of monster in human form. A demon. All those terrible things Moira had said about Fern and her family, she might just as well have been talking about herself. In fact, she probably was. It was obvious, now he thought about it. Freudian. What you see in your own heart, you start seeing everywhere.

So now he also had to ask himself, what was he going to do about it? Was he going to let her carry on spoiling his life, poisoning everything with her evil? She’d never liked Fern, never wanted her to be part of the family. Moira had probably threatened her, too, all those years ago — that must have been why she disappeared. In fact, the more he thought about it, the more likely it seemed that Moira had killed her.

Was he going to let her kill him too, now? Kill his daughter? No. No, he couldn’t do that.

He thought about a gun, but he had no idea how you went about getting one. If the TV and the tabloids were to be believed, there were pubs where you could find people who knew how a fatal mugging, or car accident, could be arranged. But Gavin didn’t know where those pubs might be. He thought about a fire, but quickly realised that would be cutting off his nose to spite his face.

He was thinking about the possibilities of drowning, when Moira screamed. He stared at his hands, momentarily confused to find that they weren’t actually holding her head underwater. ‘What the devil is that?’ Moira said, her voice sounding breathless and hoarse.

He followed her gaze and saw Bert trundling slowly across the kitchen floor.

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘The tank, I must have left the—’

Moira poked at Bert with the toe of her shoe and he hissed. It sounded remarkably like someone saying ‘Shh.’

Moira folded her arms and looked thoroughly offended. ‘Kill it,’ she said. ‘Quickly, before it gets under the cupboards or something.’

‘What? Oh, no, it’s just, it’s Bert, I—’

Her head jerked around and she stared at Gavin. ‘This — thing, this disgusting creature, it’s yours? You brought it into my house? My kitchen?’

Gavin’s lips felt too numb, too slow, to form words. ‘I—’ he managed, and got no further.

‘Oh, for heaven’s sake,’ Moira said. She took off her shoe and raised it high.

‘Don’t,’ Gavin said. He bent down and tried to scoop the cockroach up, but he was too slow. Moira brought the shoe down hard, the spiked heel slicing straight through the back of his hand. He hunched over, and vomited his breakfast muffin and coffee in a hot stream onto the kitchen tiles. It mixed with the blood and ran in little rivulets into the grouting.

Moira recoiled, her lips pinched into a tight, thin line. ‘Now look what you’ve done,’ she said.

Moira yanked the shoe back up, pulling it out of Gavin’s hand. It took some loose flesh with it. She held it at arm’s length as the nude-coloured fabric turned red. ‘These were brand new,’ she said, ‘and now I’m going to have to throw them away.’ She shook her head. ‘They’re ruined, Gavin. Do you hear me? Ruined, just like everything else.’

Gavin groaned and his vision greyed out at the edges. He didn’t realise he was falling until his head smacked against the floor and everything turned horizontal.

Moira put her shoe back on and kicked out her foot. Bert lifted into the air, tumbled over in a double somersault and landed on the floor by the sink. He froze, hissed, and carried on trundling towards the back door.

‘No you don’t, you little beast,’ Moira said, and stamped down hard. The crunch sounded very loud in the quiet kitchen.

Gavin let out a puff of air. He’d thought cockroaches were supposed to be indestructible. Supposed to survive anything. Even Moira.

‘Gran,’ Jeanette’s voice shrieked from somewhere above him. ‘Gran, what have you done?’

‘Stay out there,’ Moira said. ‘I don’t want you treading this mess through the rest of the house.’

Gavin tried to pull himself up and couldn’t manage it. His ears were ringing.

‘I said, stay there,’ Moira said. ‘Jeanette, for heaven’s — Jeanette? What are you doing? Put that down. Jeanette, I said—’ her voice cut off with a strangled, wet-sounding noise.

Gavin closed his eyes. He was so tired. Maybe he’d just lie here for a little longer.

The noises went on.

After a while, it occurred to Gavin that he should probably get up. There were things to do. He hadn’t finished making Jeanette her breakfast.

Although it was possible, by the sound of it, that she’d already found herself something to eat.

Unlikely Story

Unlikely Story

Michelle Ann King writes SF, dark fantasy and horror from her kitchen table in Essex, England. She loves Stephen King, zombie films and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Find details of her books and stories at

Michelle Ann King writes SF, dark fantasy and horror from her kitchen table in Essex, England. She loves Stephen King, zombie films and Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Find details of her books and stories at  Justin Aerni was born in Arizona in 1984. His artistic career began in 2006 when he started exhibiting his work in galleries and selling it online. He is also the author and illustrator of such books as Fighting For Fiction — 2008, Nonsense Relevant — 2009, Dead Business Men, a graphic novel in 2009, and Justin Aerni's Bitter Batter Brains — 2012. To date Aerni has created and sold over 2000 paintings to collectors worldwide and has been featured in numerous art and culture magazines.

Justin Aerni was born in Arizona in 1984. His artistic career began in 2006 when he started exhibiting his work in galleries and selling it online. He is also the author and illustrator of such books as Fighting For Fiction — 2008, Nonsense Relevant — 2009, Dead Business Men, a graphic novel in 2009, and Justin Aerni's Bitter Batter Brains — 2012. To date Aerni has created and sold over 2000 paintings to collectors worldwide and has been featured in numerous art and culture magazines.