Posted by admin on July 17, 2014 · Leave a Comment

Unlikely Story #9: The Journal of Unlikely Cartography has received a handful of nice reviews over the last few days.

Lois Tilton of Locus Online reviewed the issue, saying, “This quirky little zine always manages to pull me in with its concepts, and this one delivers a couple of strong stories.”

T.X. Watson provided a nice write-up of Carrie Cuinn’s How to Recover a Relative Lost During Transmatter Shipping, In Five Easy Steps, and also had kind things to say about our Unlikely Cartography panel at Readercon.

Last, but not least, Charlotte Ashley wrote a thoughtful and in-depth review of Rhonda Eikamp’s The Occluded for Clavis Aurea, her regular review column at Apex, calling it “an unquestionable page-turner”.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Posted by admin on July 14, 2014 · Leave a Comment

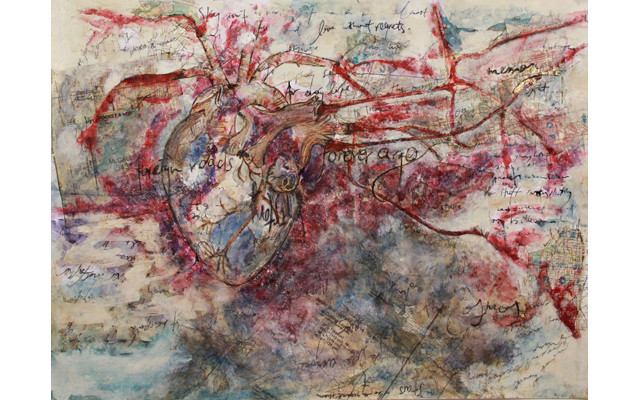

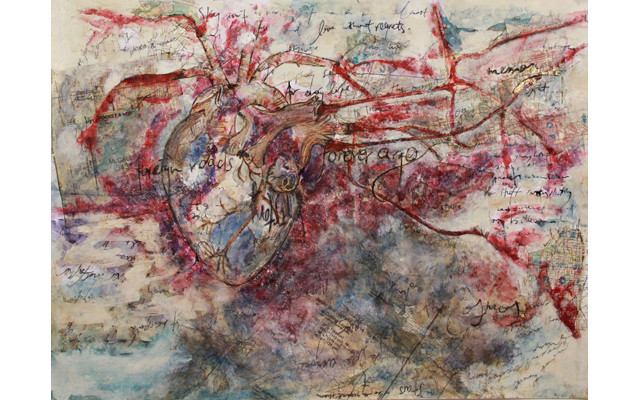

The imagery of human hearts with maps in them is quite striking and lovely. Where did the idea for this central theme in The Occluded come from?

Though I hate to admit, it came from binge-watching House MD. I’d been thinking about Unlikely Story’s cartography theme for a while. I knew I wanted to use the idea of maps in a more metaphorical sense, in a modern setting. And then those wonderful CG effects came on the screen, dyes flowing through hearts, looking just like a river delta. I still had to discover what kind of “treasure” a heart map would show the way to, who would be looking for it and why.

When you travel or visit a new area, are you the kind of person who likes to use a map (or GPS) to get to know the place, or do you prefer to explore and figure things out as you go along? Similarly, when it comes to fiction, do you outline, or do you start writing and find the story that way?

I think there are two phases — a macro and a micro level — that would apply both to finding my way physically to a new location or when writing a story. I want to find my way there — and my way home — with a map (or that GPS, preferably with a nice male voice), so I need to know the beginning, middle and end. I work out a basic story outline. The end has to be there, it’s my way home, back out of the story, so I don’t get stuck inside it forever. But once I’m there, I want to be surprised. Details — the microstructure — come while I’m writing. Serendipity happens. While writing The Occluded I happened upon an article about the copyright traps used in maps up to the 60’s — it was by chance, I wasn’t researching the story at the time — and I knew I had to work it in somehow. And sometimes the details lead me off in new directions, so that by the time I hear “You have reached your destination” I’m somewhere I hadn’t planned to be, but that’s all right too.

Authors are notorious for working strange jobs. Stephen King was a janitor and J.D. Salinger worked as the entertainment director on a luxury cruise line. What’s the weirdest job you’ve ever had, and did it inspire any stories or teach you anything you’ve used in your writing?

I spent a few months working in the natural history museum on my college campus back in the day. They somehow had the impression I was a biology major instead of languages. I just needed the money. I spent weeks typing up tags in Latin and threading them through the mouths of formaldehyde-soaked fish. I was about to have to start on the snakes when I quit. It did inspire a story recently though — a Cinderella pastiche, of all things.

One of the perennial points of contention in the world revolves around education — who should get educated (and to what degree), what should be taught, who should be excluded. Meanwhile, children in their classrooms ask, “Why do I need to know this?” Tell us one obscure thing you learned in school that you think is important, and why.

I’ve been an avid reader ever since slightly before I could read and so most of the things that interest me in life I’ve discovered and pursued on my own. Public libraries were the maps. I discovered a lifelong love of science fiction and fantasy by picking up books randomly in libraries. Two things from school that have influenced my life greatly and/or served me well respectively are languages and the ten-finger typing course I took in tenth grade. Not obscure, but not something I would have been exposed to by chance through a library.

Also, I don’t think we’ll ever see a school system where kids stay home and learn through the Internet, or at least I hope we don’t. One of the incidental effects of public education is socialization — not just kids being together, but kids learning together. It’s what we ought to be doing throughout our adult lives — learning more about life and the world together — and so I’m very opposed to home schooling.

We all have our favorite authors, some of whom everyone has heard of, and some of whom are relatively obscure. Who is one of the more obscure writers you love? What do you love about their work? Tell us which story or novel of theirs we should drop everything to read right now.

Probably not obscure since it’s been reissued, but underrated — I’d recommend The Watcher by Charles MacLean. The first few pages are not for the faint-hearted or dog-lovers, but it’s not what the rest of the book is about. Horror, paranormal or psychological thriller — I can’t even say what it is, but I couldn’t put it down.

We all start somewhere, and the learning curve from first publication is a steep one. What’s your first ever published work, and how do you feel about it now?

I have a two-humped curve — let me rephrase that. I started writing in the 90’s, published in some magazines that were the definition of obscure and some that were better-known, such as Space & Time, and then I quit for ten years. I don’t know if you would call this a writer’s block. It was a combination of getting a family going and seeing the rise of machine intelligence in the form of the Internet at around the same time. Magazines were ceasing print and going digital left and right and I felt very unmotivated by the idea that whatever I wrote would become ether. Does that make me a Luddite? Print is a beautiful, lasting thing — concrete and compact and there in your hand. If most households are like mine, where nothing’s ever thrown away, then I could always imagine someone in a hundred years finding a copy of that obscure small-press magazine in their great-aunt’s basement, reading a story of mine and being moved by it, which is the only real reason to write. I still feel funny about stories of mine that are published online. They’re children of a lesser god. But I’m working on it.

What else are you working on/have coming up you want people to know about?

By the time readers see this, I’ll have had a hand in the utter annihilation of science fiction, with a story called “The Case Of The Passionless Bees” in Lightspeed’s June issue Women Destroy Science Fiction. I also have fiction coming up in Phobos, The Golden Key, and the Fringeworks anthology Grimm and Grimmer: Black (that Cinderella pastiche). There’s a list of older stories available online at my blog. And I’ll always be watching Unlikely Story for their next quirky inspiring theme!

Rhonda Eikamp is originally from Texas and travelled a lot before settling in Germany, so her life often feels like an extended trip away from home, maps not included. When not writing fiction, she works as a translator for a German law firm, working her way through the labyrinthine maps of German legalese. Her stories can be found in Daily Science Fiction, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet and Lightspeed, with others available online through her blog at http://writinginthestrangeloop.wordpress.com.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Posted by admin on July 9, 2014 · Leave a Comment

Unlikely Story is going to Readercon! On Sunday, July 13, several of the authors featured in Unlikely Story #9: The Journal of Unlikely Cartography will be discussing maps and imaginary geography.

Sunday -- 1:00 PM -- G -- Unlikely Cartography. Shira Lipkin, Sarah Pinsker, Carrie Cuinn. This summer, Unlikely Story will publish their Unlikely Cartography issue, featuring stories by Shira Lipkin, Kat Howard, Sarah Pinsker, Carrie Cuinn, and others. Together with editors A.C. Wise and Bernie Mojzes, these authors will discuss their stories, and other authors (historical and modern) who similarly explored the cartography of the fantastic. Influences and discussion topics may include Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Eco’s Legendary Lands, Post’s Atlas of Fantasy, Mieville’s The City and the City, and more.

Maps seem to be a popular theme at Readercon this year. Are we trendsetters? We like to think so. Readercon consistently offers thoughtful discussion and insightful programming. Check out the full schedule, map-related and otherwise.

Outside of official programming, Editors Bernie Mojzes and A.C.Wise, and Art Director Linda Saboe will be at the con all weekend. Find us and say hi. We love meeting new people!

Like this:

Like Loading...

Posted by admin on July 7, 2014 · Leave a Comment

How to Recover a Relative Lost During Transmatter Shipping, In Five Easy Steps, seems like one of those titles just begging for a story, so which came first, the story or the title?

They both popped into existence at the same time. I knew, when I heard the title in my head, what the story would be about. As I wrote and revised, the structure of the story changed a little, but the title still fit perfectly, so I got to keep it.

When you travel or visit a new area, are you the kind of person who likes to use a map (or GPS) to get to know the place, or do you prefer to explore and figure things out as you go along? Similarly, when it comes to fiction, do you outline, or do you start writing and find the story that way?

I like to research ahead of time, learning the map and directions to the places I plan to visit. Once that’s settled in my head, and I can picture the geography all around me, I make a point to put the map aside and explore without it. I refer back to the map if I take a wrong turn, but if I try to rely on my visual memory, I’ll memorize a place much faster than if I wandered aimlessly or used a GPS to tell me when to turn left.

Authors are notorious for working strange jobs. Stephen King was a janitor and J.D. Salinger worked as the entertainment director on a luxury cruise line. What’s the weirdest job you’ve ever had, and did it inspire any stories or teach you anything you’ve used in your writing?

I’d like to think that everything I’ve done has inspired me and taught me. For the most part, I’ve worked a lot of office jobs. People often think of administration and management as boring and forgettable, but I’ve been able to work in vastly different industries because those skills translate from one office to another. I’ve worked for one of the largest Shakespeare festivals in the US, a non-profit law firm that specialized in getting non-violent criminals released on their own recognizance, a metropolitan YMCA, a single-doctor psychiatrist’s office, the company that created and administers the GRE test, a tech firm which makes microtools for scientists studying crystallized proteins at synchrotrons.

It was sitting around the lunchroom table with a couple of shipping clerks that made me picture a world where those low-paid, smart but not well educated, cheerfully goofy guys, could change everything, by accident. (That same week also inspired a story about buying shipping containers for fertilized dinosaur eggs, and it wasn’t even an unusual week.) Stories are everywhere. We don’t need to go looking for strange for it to find us.

One of the perennial points of contention in the world revolves around education — who should get educated (and to what degree), what should be taught, who should be excluded. Meanwhile, children in their classrooms ask, “Why do I need to know this?” Tell us one obscure thing you learned in school that you think is important, and why.

The first printing press in the United States was brought over before the country existed. In 1638, a Puritan clergyman put his wife and his printing press on the John of London, a ship bound for New England, but he died before the ship reached our shores. Luckily, his assistant, Stephen Daye, was able to establish the press in Cambridge, before Harvard University took it over.

But, wait, how did a tiny seminary school get control of the first — and at that time, only — printing press in the colonies?

When the Reverend Joseph Glover perished at sea, his press became the property of his wife, Elizabeth. So did Mr. Daye, formerly a locksmith. For £51, the cost of passage for Daye and his household (one wife, two sons, a stepson, and three servants) and the purchase of cooking tools, Glover had contracted Daye, to set up the press once they’d gotten it off the ship. Elizabeth could have sold the press, gone back to England, but she doesn’t. This 17th-century Puritan woman establishes a business, allows Daye to carry on her late husband’s work, and two years later, marries Harvard’s first president, Reverend Henry Dunster. With the press under Harvard’s protection, it wasn’t subjected to the usual Puritan rules. They printed the first book in North America, and almanacs and leaflets, including those with differing religious viewpoints. Harvard resisted attempts to limit what their print shop could produce, and set a precedent for freedom of speech. In 1781, the press was brought to Westminster, Vermont, where the colonists used it to produce The Vermont Gazette, which inspired them during the Revolutionary War.

Elizabeth ensured that printing in what would become the United States was, from the very beginning, associated with freedom, and the spread of knowledge, and almost no one knows who she is.

That story is important to me because it’s another example of women having a powerful effect on history without being remembered that way. All of us that are considered to be on the edges of society — women, people of color, those whose gender presentation and sexuality don’t conform to the “norm” of the day — we’ve always been here. We’ve always made a difference. It’s just the knowledge of that fact which is sometimes lost.

We all have our favorite authors, some of whom everyone has heard of, and some of whom are relatively obscure. Who is one of the more obscure writers you love? What do you love about their work? Tell us which story or novel of theirs we should drop everything to read right now.

That list is impossibly long. Anyone I mention will be wonderful, but there are so many authors I will fail to mention who are just as amazing. Over time, they become less obscure, which makes me very happy. I love Bee Sriduangkaew‘s work, for example, and she’s recently been shortlisted for the Campbell award, and had work appear in Clarkesworld, bought for Tor.com, and so on.

I think that reading short fiction gives you an opportunity to get to know new, young, returning, and diverse, authors. My magazines right now include Clarkesworld, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Shimmer, Apex Magazine, Crossed Genres 2.0, Lakeside Circus (see below), Lackington’s, Fireside Fiction, Strange Horizons, Interstitial Arts, Andromeda Spaceways Inflight Magazine, Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, Polyphony, Goblin Fruit, Stone Telling, and of course, Unlikely Story. If you read just one issue from any one of those magazines each month, you’ll discover something new.

We all start somewhere, and the learning curve from first publication is a steep one. What’s your first ever published work, and how do you feel about it now?

I started in journalism so my earliest publications were newspaper articles. I moved on to pop culture reviews and non-fiction articles, long before I started publishing fiction. I published in lit journals and music magazines and even wrote comic books. All of that experience was valuable; it taught be how to be a writer, and to see “literary” and “genre” as all part of the same industry.

When I finally got to submitting genre fiction to markets, it was after decades of reading, scribbling in notebooks, writing novels I recognized were… not good… My first published fiction was a poem. About vampires.

Which just goes to show that there’s always room for improvement.

What else are you working on have coming up you want people to know about?

I am currently writing two novels and a number of short stories, which I hope you’ll see soon. Later this year, I’ll have a story in the all-female Lovecraftian anthology, She Walks In Shadows; a fun piece for the anthology of imaginary tomes, The Starry Wisdom Library; some SF poetry; a couple of non-fiction essays on book history and construction. Hopefully, there’ll be a few more short story publications in there, too.

I also edit an amazing magazine of short speculative literature and poetry, Lakeside Circus. We print only work under 2500 words, to focus on the amazingly deft writing possible in shorter lengths. Please check it out online at www.lakesidecircus.com — it’s one of my all-time favorite projects.

Carrie Cuinn is an author, editor, bibliophile, modernist, and geek. In her spare time she listens to music, watches indie films, cooks everything, reads voraciously, publishes a magazine, and sometimes gets enough sleep. You can find her online at @CarrieCuinn or at http://carriecuinn.com.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Posted by admin on June 30, 2014 · Leave a Comment

How a Map Works features at least two instances of characters trying to describe a concept like ‘map’ or ‘mountain’ to someone with absolutely no frame of reference for understanding the object being described. This leads to a lovely moment between your main character and her daughter as she finds gestures and actions to convey ‘near’, ‘far’, ‘goat’, and other things Nomi has never experienced. Was the idea of communication and the ways it can break down and be mended something you specifically set out to explore with this story?

Yes! I wanted to try to figure out how you would explain the concepts in a map to somebody who had no frame of reference, as you said. But also the idea that everything on a map is a symbol in any case. We’ve accepted that certain symbols represent certain features, and we tend to think of them as universal. The challenge in the story is to find a new symbolic language when the old one can’t be used. (Your question is so well observed there isn’t really much I can add!)

Your novelette, In Joy, Knowing the Abyss Behind is nominated for a Nebula Award this year. Congratulations! How did you get the news, and how did you react/celebrate when you did?

I got a call, but then I had to keep quiet for a few days. I had dinner with good friends that evening and celebrated with an epic feast. Actually, it turned into even more of a celebration than I had planned, since the restaurant kitchen was running slow and they kept bringing us free drinks to make up for it. The catch with the phone call is that you’re not allowed to tell anybody you’ve been nominated until the list comes out officially. I was lucky enough to be eating with very good friends, unconnected to the SF community. I could trust them not to blab. Otherwise I’d still have been feasting and celebrating, but they wouldn’t have known why. Then more celebrations after the formal announcement.

When you travel or visit a new area, are you the kind of person who likes to use a map (or GPS) to get to know the place, or do you prefer to explore and figure things out as you go along? Similarly, when it comes to fiction, do you outline, or do you start writing and find the story that way?

On my way to a place, I use a map or GPS, but somewhere along the way I almost always decide I know better than what my directions are telling me, a habit which has led me to some very wrong turns. The wrong turns are often more interesting than the places I’m supposed to be, and I do love exploring.

As for fiction, it’s kind of similar. I set off knowing my starting point and my destination, but the destination is a little squirrely and sometimes changes places before I get there.

Authors are notorious for working strange jobs. Stephen King was a janitor and J.D. Salinger worked as the entertainment director on a luxury cruise line. What’s the weirdest job you’ve ever had, and did it inspire any stories or teach you anything you’ve used in your writing?

Not too many weird jobs for me. All I ever did prior to my current gig was work with horses and make music. (Or maybe those things are weird? I have no distance from it.) I worked as a horseback trail guide, and I ran riding programs at a couple of girl scout camps. I haven’t written many music stories, but there’s a ton of stuff I’ve learned from making music that applies to writing. Really, it’s a great background for writing, since I’ve been all over and passed through some very weird places. I’ve spent a night in a robot mansion, and one in a hunter’s trophy room. I found a town that doesn’t exist. Stuff like that.

One of the perennial points of contention in the world revolves around education — who should get educated (and to what degree), what should be taught, who should be excluded. Meanwhile, children in their classrooms ask, “Why do I need to know this?” Tell us one obscure thing you learned in school that you think is important, and why.

I had a teacher in primary school who took it upon herself to teach us one folk song every week (she also made us memorize poetry). I’m not sure that precise thing is the thing for everyone, but it actually was very helpful, not least because I became a folk musician. Years later, I found myself on a stage at a Phil Ochs tribute concert. There was a big closing number with everybody singing. “Can you get close enough to one of the lyric sheets?” his sister Sonny asked me. “I know this one by heart,” I said.

But folk music is often about concrete events, and it’s about people, and I think I learned a lot about history from those songs. Oral tradition.

We all have our favorite authors, some of whom everyone has heard of, and some of whom are relatively obscure. Who is one of the more obscure writers you love? What do you love about their work? Tell us which story or novel of theirs we should drop everything to read right now.

Kathe Koja wrote a novel called Skin that I absolutely adored. I should probably reread again it before I endorse it fully, since it’s been years, but I just remember being blown away by her style. I tried to emulate it for ages. It was a book about these amazing metal sculptures, and some really extreme performance art. She’s mostly written horror, I think, and I’m not a big horror reader so I haven’t read her whole catalog. I’ve got her recent YA novel, which I’ve heard is also good, but I haven’t gotten to read it yet.

We all start somewhere, and the learning curve from first publication is a steep one. What’s your first ever published work, and how do you feel about it now?

My first ever published work was probably a story I had in a Jewish women’s magazine when I was still in high school. I used it to get into Madison Smartt Bell’s writing seminars at Goucher. I found it recently, and I have to say it’s not too bad. A little adverb heavy and a little dramatic, but readable.

What else are you working on have coming up you want people to know about?

I’ve got a half-finished novel, and in the wings, an idea for one set in the world of this story. Other than that, I’m really happy to have a flash piece in Lightspeed’s Women Destroy Science Fiction! Issue, which is out this month. I have a couple of other pieces in the queues at Lightspeed and Asimov’s that I’m very pleased with as well.

Sarah Pinsker is the author of the novelette “In Joy, Knowing the Abyss Behind,” a 2013 Nebula finalist and 2014 Sturgeon Award finalist. Her fiction has been published in magazines including Asimov’s, Strange Horizons, Fantasy & Science Fiction, and Lightspeed, and in anthologies including Long Hidden, Fierce Family, and The Future Embodied. She lives in Baltimore, Maryland. She can be found online at www.sarahpinsker.com and twitter.com/sarahpinsker.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Posted by admin on June 22, 2014 · 1 Comment

Table of Contents

How a Map Works by Sarah Pinsker

How to Recover a Relative Lost During Transmatter Shipping, In Five Easy Steps by Carrie Cuinn

The Occluded by Rhonda Eikamp

All of Our Past Places by Kat Howard

This Gray Rock, Standing Tall by James Van Pelt

The Cartographer’s Requiem by Shira Lipkin

Editor’s Note:

Last year we ran a contest of sorts to help us choose the title (and theme) of this issue, and when Sarah Pinsker first suggested “Unlikely Cartography,” my instant reaction was, “Yes, that.” I have loved maps since before I knew what they were. I remember when I was young, pulling my father’s topographic globe off the bookshelf and onto the floor, running my hands over it and, when my dad walked in to find me sitting amidst a heap of fallen books, asking, “What is this?”

By which I meant, of course, “What is the meaning of the signifiers, both graphic and linguistic, spread across this strange ball?” I didn’t have all those words yet, of course, since I had only just started learning my alphabet, but my dad understood. It became a new game for us: I’d spin the globe, close my eyes and put my finger down. When the globe stopped, my father would tell me a story about the people who lived there.

Maps describe the world — not just as it is, but as it is seen by the people making the maps, incorporating their worldview, their (often unstated and unexamined) predispositions and their concerns and interests. A map might show political boundries or geological features, might show safe waters for shipping or house prices in a neighborhood. It might show you how to get from one place to another.

At the same time, a map defines the world. A line on a map dictates languages, laws, opportunities, possibilities. Change the lines on the maps, and reality shifts to adjust.

The stories that follow encompass all of that, as the characters search for themselves, for those they have lost, and for those they have yet to find, and, as one does when one keeps one’s eyes open, find more than they expect.

Bernie Mojzes

June 2014

Cover art by Vivian Gu

Like this:

Like Loading...

Posted by admin on May 5, 2014 · Leave a Comment

In the spirit of our issue of deliberately terrible fiction, we asked our authors some deliberately terrible questions. Luckily, they were kind enough to play along. Here’s what Kelda Crich, author of All Flesh is Grass had to say…

Where do you get your ideas?

I tell you where I don’t get them, and that’s my dreams. Last night I dreamed of needing some milk. And in my dream I nipped to the corner shop and bought some. I don’t even drink milk. Sleeping: what a time-waster.

Have you written anything I’ve heard of?

I was once published in Misty. When I was ten. Misty was a very famous spooky land girls’ comic in the UK. I’m sure you’ve heard of it. I sent them a spooky joke.

Nope, I haven’t heard of that. Have you considered writing more like Stephen King or J.K. Rowling? They seem to be pretty popular and rich, so maybe you should do that.

Do they write stories about nipping to the corner shop and buying milk? Because I’ve got plenty of them. Also skeleton jokes.

I have a really great idea for a story about a cowboy and an astronaut who are best friends. It’s kind of like Toy Story, except set during the time of The Great Gatsby, only it takes place in the Lost City of Atlantis. Robert Redford would be perfect for the movie version. Why don’t you write it, and we can split the profit 50/50? Maybe 70/30 since I came up with the idea and that’s the hard part. What do you think?

You fool. Did you copyright that idea? Because somebody might steal it. You can copyright an idea by writing it down and then posting it to yourself. The stamp’s frank proves the copyright privilege. But never open the envelope. To be extra safe, write @ after every original idea. (It should be c in a little circle, but I don’t have one of those on my keyboard.)

And on a slightly more serious note (but only slightly), given your story is gracing the fine pixilated pages of an issue of deliberately terrible fiction: Do you have any regrets?

What? Terrible fiction? I . . . Is it too late to withdraw?

Kelda Crich is a new born entity. She’s been lurking in her creator’s mind for a few years. Now she’s out in the open. Find her in London looking at strange things in medical museums or on her blog: http://keldacrichblog.blogspot.com/. Her work has appeared in Lovecraft Ezine, Spinetinglers and the Life After Death anthology.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Posted by admin on April 28, 2014 · Leave a Comment

In the spirit of our issue of deliberately terrible fiction, we asked our authors some deliberately terrible questions. Luckily, they were kind enough to play along. Here’s what Brynn McNabb, author of Why, Ethan, Why?!?!? 🙁 had to say…

Where do you get your ideas?

I grow them in a window box. I get the seeds for cheap at the farmer’s market.

Have you written anything I’ve heard of?

Well, I write short fiction, so--

Nope, I haven’t heard of that. Have you considered writing more like Stephen King or J.K. Rowling? They seem to be pretty popular and rich, so maybe you should do that.

I considered it, but it would just be too easy.

I have a really great idea for a story about a cowboy and an astronaut who are best friends. It’s kind of like Toy Story, except set during the time of The Great Gatsby, only it takes place in the Lost City of Atlantis. Robert Redford would be perfect for the movie version. Why don’t you write it, and we can split the profit 50/50? Maybe 70/30 since I came up with the idea and that’s the hard part. What do you think?

I’m sorry, I only pay flat rate for ideas, and it sounds like you’ve just given me most of your idea for free. Good luck proving I didn’t come up with that on my own.

And on a slightly more serious note (but only slightly), given your story is gracing the fine pixilated pages of an issue of deliberately terrible fiction: Do you have any regrets?

Sure. I should’ve married a doctor.

Brynn MacNab is uniquely qualified to present this story, as she is secretly the princess of an unpronounceable--I mean, exotically named--land. She is deeply offended to be included in the Journal of Unlikely Story Acceptances, although something like this was bound to happen sooner or later. She has been writing fantasy for far too long to continue to get away with it. If you would like to subject yourself to more of her published stories, you can find them at brynnmacnab.blogspot.com.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Posted by admin on April 21, 2014 · Leave a Comment

In the spirit of our issue of deliberately terrible fiction, we asked our authors some deliberately terrible questions. Luckily, they were kind enough to play along. Here’s what Andrew Kaye, author of Whinny If You Love Me: A Love Story had to say…

Where do you get your ideas?

The usual places: In the smiles of good friends. The laughter of children. The warm embrace of costumed superheroes. The bathroom.

Have you written anything I’ve heard of?

I’ve lately grown bored with traditional writing, and I’ve branched out into new and exciting techniques. My last project was an epic fantasy novel called The Great Ring of Power: The Adventures of Dick Malicious, Wizard First Class: A Fictional Novel in Three Parts: Episode 1 of 9 of the Malicious Circle Series. The novel was written entirely in condiments on over 200 slices of bread. You probably haven’t heard of it though because the bread went moldy and I had to throw it out, but my cousin took pictures of each slice and I’ll upload them on deviantART once he remembers the code to his cell phone.

Nope, I haven’t heard of that. Have you considered writing more like Stephen King or J.K. Rowling? They seem to be pretty popular and rich, so maybe you should do that.

I have to disagree with you. My young adult fantasy novel Dick Malicious and the Sorcerer’s Stone hasn’t been selling very well. And my horror novel The Squirts, which is about a sentient fire hydrant that starts murdering children in a small suburban town, has performed pretty poorly as well. I think the real money is in imitating Tolkien. It’s worked for a lot of authors so far.

I have a really great idea for a story about a cowboy and an astronaut who are best friends. It’s kind of like Toy Story, except set during the time of The Great Gatsby, only it takes place in the Lost City of Atlantis. Robert Redford would be perfect for the movie version. Why don’t you write it, and we can split the profit 50/50? Maybe 70/30 since I came up with the idea and that’s the hard part. What do you think?

I think if you change Toy Story to The Last Unicorn, The Great Gatsby to The Age of Innocence, and the Lost City of Atlantis to the Cloud City of Bespin, you might have something I could work with. Robert Redford would be perfect for the role of Manny Coreman, the tough-as-nails robotic manticore I’m envisioning.

And on a slightly more serious note (but only slightly), given your story is gracing the fine pixilated pages of an issue of deliberately terrible fiction: Do you have any regrets?

I regret nothing!

Andrew Kaye hails from the suburban wilderness of Northern Virginia with his wife and kids. His (definitely not terrible) fiction has appeared in Daily Science Fiction and Electric Velocipede, among other fine magazines. When not writing, Andrew draws cartoons and edits the humor magazine Defenestration, which are parts one and two of his seventeen-step plan for world domination. Feel free to bother him on Twitter @andrewkaye.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Posted by admin on April 14, 2014 · Leave a Comment

In the spirit of our issue of deliberately terrible fiction, we asked our authors some deliberately terrible questions. Luckily, they were kind enough to play along. Here’s what Siobhan Gallagher, author of Twisty had to say…

Where do you get your ideas?

Everywhere. Though for “Twisty” it’s the dissatisfaction of a poorly done twist (or many twists). I suppose an alternative title for this could’ve been, “Dean Koontz: Why the The Taking sucks!” But maybe that’s too extreme…or not extreme enough.

Have you written anything I’ve heard of?

Well I do have this one piece--

Nope, I haven’t heard of that. Have you considered writing more like Stephen King or J.K. Rowling? They seem to be pretty popular and rich, so maybe you should do that.

Why not do one better and write horrific tales of horror for children? Money maker right there!

I have a really great idea for a story about a cowboy and an astronaut who are best friends. It’s kind of like Toy Story, except set during the time of The Great Gatsby, only it takes place in the Lost City of Atlantis. Robert Redford would be perfect for the movie version. Why don’t you write it, and we can split the profit 50/50? Maybe 70/30 since I came up with the idea and that’s the hard part. What do you think?

Sure! And we’ll call it “Dr. Strangelove Rides Again”.

And on a slightly more serious note (but only slightly), given your story is gracing the fine pixilated pages of an issue of deliberately terrible fiction: Do you have any regrets?

My only regret is that I don’t have more tea. But really, if some sort of joy or entertainment value can be derived from a piece of fiction, is it still bad? …Well yeah, probably is--but at least it’s not boring! Boring fiction is the worse. Perhaps that’ll be the next year’s issue, Unlikely Boringness.

Siobhan Gallagher is a wannabe zombie slayer, currently residing in Arizona. Her fiction has appeared in several publications, including AE -- The Canadian Science Fiction Review, COSMOS Online, Abyss & Apex, and the Unidentified Funny Objects anthology. Occasionally, she does this weird thing called ‘blogging’ at: defconcanwrite.blogspot.com.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Unlikely Story

Unlikely Story