All of Our Past Places

By Kat Howard

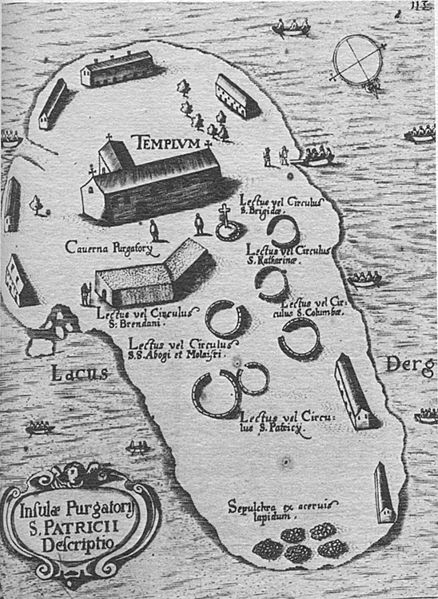

Thomas Carve Lyra sive Anacephalaeosis Hibernica 1666 Insulae Purgatory (Public Domain)

Aoife always told me that you could go anywhere, as long as you had the right map. So when it happened, my first thought, when I let myself into her apartment after not hearing from her for three days, was this weird feeling of pride. She’d done it. She was gone.

Then the fullness of what had happened hit me: She was gone.

I checked, and checked again.

Her apartment was nearly empty. The refrigerator had a couple of cartons of takeaway whose contents ranged from edible to Dear God, and cream for her coffee. The usual.

And then, there were her maps, covering almost every flat surface in the place. The ones she had collected, the ones she was sure were the way there.

All of the maps that had St. Patrick’s Purgatory marked on them had been unrolled, tacked flat, arranged one on top of the other. I was sure there was a reason for their order, and that I would have understood it if I were Aoife. Whatever the reason was, though, without her I couldn’t parse it. What I could see was that, on each of the maps, St. Patrick’s Purgatory was gone. In its place, a small hole with burnt edges.

With the maps arranged as they were, the burnt-out places were all exactly the same, as if a fire had caught, right there, and then been immediately extinguished.

I yanked my hands away, stepped back from the table, and reminded myself that I was being ridiculous. People didn’t go to Purgatory, or if they did, it was after they were dead. If they went to St. Patrick’s Purgatory, that blip on the map of Lough Derg, Ireland, it was by taking a ferry to Station Island. They didn’t go by disappearing into a map, like some faux-charming “this is how our story begins” cold open from a crappy animated movie.

Except. Aoife was gone. And there was a hole in each map in the place where St. Patrick’s Purgatory had been.

The thing, of course, that’s supposed to happen in a situation like this is that you follow the other person to the Underworld. You bring them back. I mean, I’d been around Aoife long enough to be familiar with the stories. I knew the rules. Someone went to the Underworld, someone else came to get them, and then things didn’t work out. The end.

Still, as far as underworlds and afterlives went, Purgatory was a little different. The writers who’d claimed they’d been had also usually claimed that God sent them back to tell the story.

Let’s be honest. I had no idea what sort of framework I was operating in here, but waiting around and relying on God to zap Aoife back home so she could write about her Purgatorial experiences in verse as if she were Dante wasn’t a plan I could get behind.

If there was going to be a way out of this mess, the maps would be the key. That was how things worked: if you wanted to get somewhere, you needed a map. The only problem with that was, whatever Aoife had done had erased St. Patrick’s Purgatory from them.

Places disappear from maps all the time. Maps from today will not include Czechoslovakia, East Germany, or the Free Independent Republic of West Florida. There are reasons for these disappearances: places choose new names, wars are fought, peace is won. It sounds simple, but it isn’t. We say the borders of countries are just lines on a map, but places run deeper in us than that.

When Aoife and I were in high school, the boundaries of Prussia had been an ongoing joke in our AP European History class. Constantly altered by reasons of conflict and history, it seemed as if they had been redrawn on a whim, traced one way and then the next with the specific intent of frustrating us, all those years later.

We never gave any thought to the people in those redrawn boundaries. We never asked ourselves what happens when a country is literally erased from the map.

We met because of a map, Aoife and I. When we were kids, Aoife would make what she called atlases. It’s as good a word as any for them, I guess. She would take maps, any kind she could get her hands on — the kind you buy on impossible-to-fold paper at the gas station, or from the blue-edge chunks of appendix at the back of social studies books, or once, the surface of a globe, peeled and laid flat, and she would cut them into pieces and tape them back together.

They were impossible to use if you were actually trying to get somewhere. The last time I checked, Mordor has no contiguous boundaries with Bismark, North Dakota.

She’d walk around the neighborhood with them, a cartographer examining her work. One day, she was standing at the bottom of my driveway, pencil in hand, making notes.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“Checking locations,” she said, looking from the plum tree in the yard back to her map and nodding.

“Why?”

“So the map will be right. So I can go.”

“Go where?”

“Wherever I want. Somewhere else.”

“Can I come with you?”

She looked at me, very seriously. I fidgeted under her scrutiny, raising one foot up to scratch at a mosquito bite behind the other knee.

“Okay,” she said finally. “I’m Aoife.”

“I’m Miren.”

After that, we went everywhere together. Until she went to Purgatory.

So, I would need a map. A map to go to Purgatory, to get Aoife back. I left her pile of maps untouched, afraid that if I moved them, it might close whatever door it was she had opened.

I went back to the beginning, to the maps Aoife had made when we were kids. Her atlases. They were carefully folded, and stored inside a cedar chest that had seventeenth century shipping routes carved on its lid.

She never let me help make them, those summers of fourth and fifth and sixth grade. I could go on the adventures, but she always picked the places, always was the one to craft our way there.

I never fought with her about that. Even then, I knew she was the one of us who needed to get away.

I opened the chest to find it packed full of maps, folded one on top of the other. Taped and stapled pages creating countries that never existed. I shook my head at myself, acknowledging the ridiculousness of what I was doing, and began unfolding them.

They smelled like youth and summer. Like dried grass and melted ice pops that turn your tongue neon blue. Like the coconut of sunscreen and the dull plastic scent of bandaids. Grains of sand fell from them to the floor, and I found a piece of a crayon wrapper — one of the darker blues — and the orange and black wing of a butterfly, still bright.

Mile markers of our summers, of going anywhere but here, of finding all of the possible somewhere elses, of always feeling found, as I walked on those impossible quests of Aoife’s, even though I never knew from day to day where we were going.

The one place I never walked her to was her house. “It’s better if we go to yours, Miren. We need a fixed point, like True North.”

I had seen the bruises on her arms, heard my parents talk about Aoife’s dad when they thought I wasn’t around, so I understood, a bit, why she needed a reason to center the maps somewhere other than her house.

“Plus, I live on Rose Avenue,” I said. “Like a compass rose.”

“Exactly,” Aoife had said, and her smile had bloomed across her face.

I brushed my hand across my eyes so my tears wouldn’t fall on the maps and obscure them.

We think about maps like they are a kind of great truth. Like, if you find the right one then you’ll know the one true way to where you’re going, and you’ll be able to get there safely, on the most direct path. The straight and narrow, that avoids both the woods and the wolves within them.

But as anyone who’s ever gotten lost while reading a map, or stopped just short of the lake their GPS was trying to drive them into knows, it’s never quite that simple.

Maps are often made with small, deliberate errors, cartographers watermarking their work. Paper towns and cartographic graffiti. Sometimes the errors persist, and we navigate around someone’s imaginary land. Sometimes, you just keep going, astounded when you don’t run out of road.

Even when she stopped making maps of her own, Aoife never lost interest in them. She was my best friend, so I adopted her obsessions as my own. It was what you did, when you were eleven, twelve, and I never grew out of it. I studied cartography. I learned how to draw a compass rose, and the difference between a sidereal rose, and the classic twelve-wind rose. I drew them in the pages of my notebooks, increasingly elaborate in their construction, full of symbols for the winds, whose names I wrote out in all the old languages of map-making.

I got comfortable with the idea that there are monsters in the margins, and when I turned eighteen, I had HIC SVNT LEONES tattooed on the inside of my left wrist: “Here are lions,” the words that denoted unknown territories. Aoife went with me, and had “Ultima” written on her left ankle, and “thule” on her right. Another phrase from the edges of maps: “Past the borders of the known world.”

Like wherever she was now.

It was the old maps, the ones with things like HIC SVNT LEONES on their outermost margins and sea monsters drawn in their oceans, that started Aoife’s obsession with Purgatory. There was this map from 1492, by the cartographer Martin Behaim. It was meant to be a map of the entire world. The only thing marked on Ireland was St. Patrick’s Purgatory.

Aoife cocked her head, and traced her finger over the tiny, mostly-unmarked, Ireland. “Hmmm,” she said. “Why does this place matter so much?”

That started a flurry of searching for other maps, looking for ones that had St. Patrick’s Purgatory marked. I waited for this to be a thing like her earlier obsessions, for her to begin making maps that were palimpsests of instructions to the Underworld, that sent Inanna walking side by side with Persephone.

“They call it the Forgotten County, you know,” Aoife said, bent over a stack of books and papers. “County Donegal. Where St. Patrick’s Purgatory is. Parts of it permanently depopulated during the Famine. Whole towns just disappeared from the map. Even today, it only has just over half the population it had when the Famine started.”

Lost and disappeared. “Seems like the kind of place where you might find Purgatory, then.”

There were people who said they had. Old, old stories. Some medieval knight who actually slept in the cave on Station Island, the actual St. Patrick’s Purgatory, back when you could still do that. When he woke up, he said he’d had visions of Purgatory, before Dante was even born. So it’s not like Aoife was the first person to think the place really was a gateway to Purgatory.

But I am pretty sure she was the first person to think she could get there through a map.

She scoured the internet for them, bought any map she could that had St. Patrick’s Purgatory marked, regardless of provenance or condition. Some were torn and stained, burnt. Some were barely more than fragments. She kept them all.

“How many do you need?” I asked her.

“Enough to have confidence in the boundaries.”

“I’m just going to remind you again that for the money you’ve spent collecting these, you could have bought multiple trips to Ireland.” I set a plate of pasta with butter and cheese next to her, hoping she would eat.

“I keep telling you: I’m not trying to get to Ireland. I’m trying to get to Purgatory.”

It was like walking backwards through our childhood, looking through Aoife’s maps. Not just in the sense of nostalgia, but in the sense that these maps were our compass rose, illuminating the cardinal directions of our past. I hadn’t known, then, what she was making when she put together these atlases, hadn’t realized that she was making maps of us.

There was a map made up of all of the cities we had said we wanted to live in when we grew up, choosing them only by the sound of their names: Shanghai, Abu Dhabi, Kilkenny. There was another made of some of the countries we wanted to travel to, Prussia in the center because, as Aoife said, no place deserved to disappear forever. Our own city, sliced into pieces and collaged with maps of impossible places — Atlantis and Avalon.

I looked at that one carefully, looking for a border in common with Purgatory, but no. Only the River Lethe, cut from its banks and spiraled on top, connecting all of them like a thread.

Aoife was still gone.

I marked on the calendar all the days I thought she might come back — feast days and holy days, forty days and forty nights, and other dates from other pilgrimages to the lands of the Dead.

“Dead,” I said out loud, letting the weight of the word fall flatly against the air in this room full of maps. I said it again: “Dead.”

Because of course, it was possible. Possible that she hadn’t passed through the maps like a glowing spark, possible that she hadn’t gone to Purgatory at all, at least not as a living woman, but was somewhere else. A body, not Aoife. Possible that, even if she had gone to Purgatory, there was some sort of expiration date on her visit, that when her visa expired, she wouldn’t get deported, but instead made like all the other souls there.

I didn’t say it a third time.

Cartography, the making of maps, is based on the idea that we can model reality. When it comes to a map, the reality being modeled is usually some kind of physical location.

I looked at the room I sat in, covered with Aoife’s maps. Maps that modeled no reality, except the one she wanted them to have, the River Lethe as red thread connecting the pieces. Maps to places she imagined into being. Maps to the places we once were.

A pile of maps, Purgatory burned through, erased from existence. You could go anywhere, so long as you had the right map.

That was what I needed, if I was going to bring Aoife home again.

I left Aoife’s for the first time in days, blinking wraith-like against the sun, walking a path of circles through all the places that had been our maps. I gathered take-out fliers from our favorite restaurant, with their delivery ranges hand-scribbled over the dessert list, and folded concert posters from the club we snuck into with bad fake ID’s to dance at, directions stamped in the bottom right corner, and an old history textbook from our high school, one that had a map of Prussia in it. Bits and pieces of our reality.

I took them back to Aoife’s, and got to work. First, I drew the compass rose, sidereal, because the stars were everywhere. All thirty-two points — the rising and setting positions of the brightest stars in the Northern Hemisphere, with myself as Polaris in the North and Aoife as Sigma Octantis, the true Southern pole star, which is almost impossible to see unaided. Then I cut pieces from all of the things I had gathered this afternoon, and all of the maps Aoife had made.

I cut the burnt-out center from one of Aoife’s maps that had showed St. Patrick’s Purgatory, a reproduction of Behaim’s, the map that had started all of this. A map should reflect reality, and I would use that piece as the blinking “you are here” icon that would help her find her way home.

I fit all the pieces together, taping them tightly, until the borders between one and the next were erased. When it was almost complete, I wrote the words HIC SVNT LEONES, not at the traditional place on the margin, but over the one place on the map I was unsure of. The center. Purgatory. The last piece I fit in the map was the marker for St. Patrick’s Purgatory. I had mended the burnt out spot, made sure that it was no longer missing from the map.

And nothing happened.

I thought it would be enough — finish the magic, bring back Aoife. But nothing.

I closed my eyes tight, and clenched my fists until my hands hurt. She was gone. Really gone, and I didn’t know how to find her.

Once I felt like I could breathe again, I got up. I folded all of Aoife’s maps, the atlases, and put them back in the chest. I set my map on top of all of her maps of Purgatory.

Maybe I would buy a ticket to Ireland, go to Station Island. To a Purgatory, even if it wasn’t the one where Aoife was, where I could atone for not knowing how to find my lost friend.

It was dark when I walked home, but I knew the way. My parents’ home, that I had come back to for the summer, between college years. Knew it well enough to walk it half-blinded by tears and exhaustion.

“So hey. Nice map. You ended it at your house, though, not mine. Still our True North, I guess.” Her voice was rough — a glitch recording. She stood up from the front step, stumbled, then caught herself on the doorframe. “Thanks for bringing me home.”

Aoife.

“How?” I asked.

“Just like the way there. Through the map,” she said, hugging me.

Her hair smelled like stale earth, and I could feel the knobs of her spine. Her hands dug into my arms. “I couldn’t find a map. After I got there, after I realized I wanted to go home, I spent the whole time looking. But I couldn’t find one. Not until you made it.”

I didn’t ask, not about anything. Not then. I just held her, held her here, a fixed point in a map of turning stars.

Unlikely Story

Unlikely Story