Ink

By Mari Ness

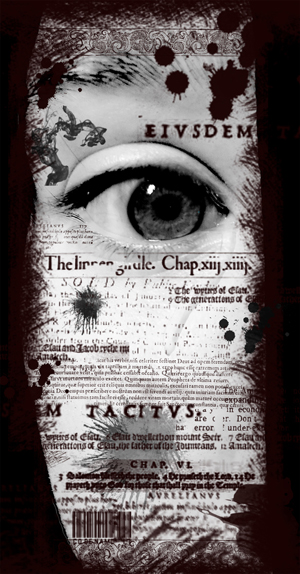

Illustration by Ula Jemielniak

The Story by Ula Jemielniak

Trying to get the words out of her hands is the worst part. Easy enough to get them in. Message received, hurried meeting at a coffee shop, a restaurant, a train station, a park, a delicate or careless removal of gloves on both parts, a handshake, a touch on the cheek to ensure that every word is there, quick and careless goodbyes, as the words sink down beneath her skin and begin playing inside her hands causing a horrible, desperate and still not quite familiar itch, as she hurriedly covers them with gloves, dark and leather and (she hopes) completely opaque.

She’s even enjoyed many of these meetings. She finds a certain romance in the hurried encounters at train stations and parks, while the conversations at coffee shops and restaurants are sometimes stimulating, delightful, amusing. (Sometimes. Some of the agents sent to her are, in a word, dull. Or dour, which is just as bad.) She is occasionally afraid that someone — a neighbor, perhaps; one of the waiters; one of the attendants at a park, or train station, will notice, will think her a flirt, or far worse, a loose woman, given the number of people she has allowed to touch her hand and skin.

Not that she’s ever taken any of them home, of course (despite several and sundry temptations), or touched anyone’s upper limbs, above the wrist, nothing more than a hand, but the laws can be rigorous. Very rigorous. Fortunately, if she is to be truthful with herself, she is not the sort of woman people notice: not ugly, certainly, but not beautiful, either: medium height, medium build, brown hair, brown eyes, a straight nose, nothing that would stand out in a crowd, age anywhere from twenty to forty. It is why, after all, she was chosen for this.

Not, evidently, for her skill in getting the words out.

It’s supposed to be simple enough. Place your hand flat on the paper, still the mind, and allow the letters and words to leach out, one by one, onto the paper. That, supposedly, is where the trick comes in. Followed by the next trick: sorting the words into some sort of sense. After all, even this method might not be totally safe, even with the random nature of the meetings and the messengers; she never returns to the same spot until she has been to at least four other places, and almost never meets the same messenger twice. (And when she does, she can’t help noticing it’s always one of the dour ones.) So, a failsafe: the messages are sent in code, or sent with the words in random order, to be deciphered.

The transcribed messages then written in a new code, and engraved on her own hands from the black ink the coders had given her in their one meeting, to be passed along to the next messenger with the briefest of touches. Or — far more rarely — placed in the same cream colored envelopes that tell her where to meet each messenger, left in her own fireplace among the cold ashes.

It all has to be done quickly, while the message is still fresh.

It all has to be done quickly, before anyone sees the letters swirling just beneath her skin.

It all has to be done quickly, while the letters are still there. While they can still leave her skin.

She never waits to see the envelopes leave the cold fireplace, only heads out, shivering, to a coffee shop, where she places her hands around a warm mug and tries very hard to tell herself they do not itch.

She has sometimes been too late. Sometimes, she’s missed the original envelopes, or opened them too late, to find only words that have faded long past reading. At such times she panics; she has been told what might happen if these messages go astray, what could happen. She even thinks she has heard hints about what has happened after those messages have been lost, in later messages left inside her skin.

She tries not to think of those hints, of what they mean, but they creep inside her at night, along with some of the words from other messages, messages she does understand.

She tries not to think about how many times she has almost failed. Or has failed.

She can’t lose another message.

She can’t lose this.

If she loses this, she loses everything.

Her employment, little though it pays her (“You work for Truth, for Justice, for Thought,” they had told her, three things that do not, apparently, translate cleanly into coin. Sometimes, waiting for that coin, she gets very hungry; it is one reason she is so delighted by the rare meetings in restaurants, where the dinners are usually paid for by the other messenger.) The glimpses she gets of other worlds, other moments, other lives, of things important and unimportant, of tales she would otherwise never hear. Her regular outings, which, brief as they are, constitute her only socialization.

(Agents do not make close friends, she has been warned, not with regular people. Dangerous for her; deadly for them. She has seen many hanged, and she does not argue this point. Besides, what would she tell any friends that she made? I meet people, and collect letters into my hand, and draw these letters out, and send the messages on through other hands, other paper. I don’t even know what they mean. I receive bronze coins for my efforts, and I have adopted a small kitten, to keep my hands busy between assignations.)

Her purpose.

Her justice.

“Do you want revenge?” she had been asked, during her only interview, an interview where the two cloaked and hooded people (men? women? she spent nights wondering, but could never be sure) had never let go of her hands, never stopped examining them and turning them.

“I’m past that now,” she had said calmly. (Not entirely truthfully, but she was a realist; revenge — real revenge — was beyond her.) “But others need justice.”

It might have been that, or something in her hands, that made them give her a pen and sign her own hands, first her right, and then her left, before having her sign the gloves they wore.

(She had never touched their skin. This, too, still bothers her some nights: all of the other strangers that she has touched, almost caressed, all of the other hands that she has clasped, and yet she never once touched the skin of those who employ her.)

She can’t. lose. this.

She is not very good at it.

She is terrible at it.

But surely, all she needs is practice.

She tries everything she can think of. Pacing. Not pacing. Putting her hands against the paper for an instant longer. An instant shorter. Deep breathing. Shallow breathing. Jumping up and down. Humming. Singing. (Banging sounds against her walls after that; her neighbors are not that charitable.) Thinking of nothing. Thinking of everything. Thinking of words. Thinking of ink. Trying not to think oh please come faster please come faster I will lose you if you do not come faster.

She takes a knife to her hands, to free the words more swiftly.

Disaster. The blood rushes through the paper, rendering it unusable; every letter in her hand vanishes, in an instant. She finds herself rocking back and forth on the edge of her bed, spreading blood across her face before she realizes what she is doing. Shock. She staggers to her tiny kitchen — not a kitchen, really; a small alcove with a tiny cabinet where she stores a few biscuits and jars of dried fruit, with a tiny table where she keeps a bowl and a basin of water. She washes her hands and binds them up, thinks a bit better of it, retrieves her few small bronze coins from under the bed and heads out to an apothecary’s to find an antiseptic. It costs nearly her entire hoard, but he has not just the antiseptic, but — it’s difficult to believe — a tiny flask of real alcohol. That, and some strange bark, crumbled into water, should dull the pain and hurry the healing. She will tell no one of the bark, of course. It’s forbidden.

The apothecary has seen her, she thinks. She trembles.

She does not leave her room for two days, her eyes fixed on the cold ashes in her fireplace, until at last she remembers that the messages never come when she is watching the ashes, only when her eyes are turned, and that she will freeze in any case if she stays here much longer. She stuffs her hands, still aching, into her armpits and walks the city streets for several hours, looking at no one, stopping only to buy a small meat pie, which she eats hurriedly, letting it burn her tongue and the inside of her mouth.

She has to get back.

The trick has worked. Another envelope, cream colored, on the ashes. She rushes forward, stops, remembers that she needs to wash her hands first. That was explained. She fetches new water for her pitcher and her bowl, pulls off the bindings, washes her hands. They are healing nicely. They can take words now, yes they can. She is certain of it.

She opens the envelope.

A symbol.

Explanations are requested.

She writes her response carefully, thoughtfully, using every tiny space of her fingers and her palm, hoping that whoever she meets has large hands. It is true, she admits, that she has had problems getting the words out of her fingers. But she is still new at this, still had only a few years of experience. She needs more assignments. More practice.

As she writes, some of her cuts begin to bleed again. She hopes they do not smudge her words.

Also, she needs more ink. She sets that sentence in the third finger of her left hand, to ensure it is not lost.

The meeting, at a train station, is extraordinarily brief even by her standards — a quick bump against her arm, a hurried apology, the briefest of hand touches before the man leaves. She hurries to pull her gloves back on — did anyone notice? Did anyone see? Everyone watches — and hurries home to her cold fire, feeling the dual sting in her hands. The itching that is almost always there, that has almost always been there since they first put ink through her skin, and a new itching, from the once again open wound.

When she returns, another cream colored envelope is on the ashes. She peels off her gloves, wincing, and washes her hands carefully. And the gloves; she will probably need a new pair. More of that bark. More of that antiseptic. More of that — She has no money. She opens the cream colored envelope, trembling.

No one could have received her response yet.

Another symbol.

She has been found.

She shakes.

The apothecary? Someone else? Everyone watches, she had once been told. Everyone. That isn’t important now. She reads on.

She is not to worry. Despite her low execution rate — her hands flare up — they have determined that she has a certain gift for codes. She can therefore petition to be allowed into one of the secure centers, where she will be assigned to focus on code development and breaking. The centers are, they repeat, secure, although of course their locations cannot be revealed at this time. If she chooses this option she will be cossetted, allowed to choose from a wide variety of luxury items, foods and entertainments when not focused on her duties. She will not be seen by anyone except one or two other highly trusted agents; she will be kept far away from any window or door to prevent the slightest chance of discovery. She will be confined to four rooms. She will remain there until she is forgotten. They cannot say when this might occur.

Alternatively she may choose to continue her duties in a new city at a distance of at least one thousand miles from her current location. For security reasons she will be given a slight memory wipe, which will force her to learn the entire process again upon relocation. A new bottle of ink will be provided, but they cannot guarantee food, clothing, or shelter. She will have no money until at least three executions have been completed. She is advised to execute discretion with these funds and later meetings even in this new location; she has been found. She could be found again.

She can resign.

They do not advise this.

Forgotten.

She looks around her small room, with its little alcove and table, the small cot that she has covered with old blankets to make a little more comfortable. She thinks of everything that has brought her here. Truth. Justice. Thought. She thinks of the other agent she had dinner with, two weeks — three weeks? — ago, the flash of desperation in the other woman’s eyes.

The way she knows no one in this city, not even those whose hands she has touched.

The way the rain has pounded into her shoulders and skin as she hurries back to her small room to get the words out of her skin.

The ink begins to fade from the message. Her hands are blank. She knows where she is to meet the agent who will pass on her answer.

Reassignment, she writes on her hand. I will let you name the city.

Her hands itch as she hurries out to the coffee shop.

Unlikely Story

Unlikely Story