Meltdown in Freezer Three

By Luna Lindsey

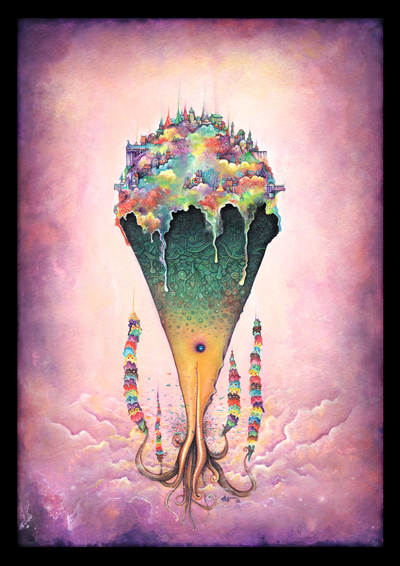

Illustration by Simanion

Neapolia by Simanion

There’s a lost city in the back of my ice cream truck.

It’s in the third freezer — the reassuring one, not the mean one — where I used to keep the Rocket Pops. I emptied them out when I found the faeliens living there.

It’s 107 degrees outside. Heat wave. Taneka Truck is an old woman, spry and cranky, with weak joints. I had her retrofitted to self-drive when I bought her because I’m a very bad driver. Ms. Truck doesn’t want to retire. She keeps the ice cream and me and the lost city all nice and cold and protected from the March sun, even when it pries at the windows with molten fingers.

I slide open the side window, though he’s stubborn as usual, to let the kids lean in. This window hates his job, having to move all the time. He’d rather stay still. He aspires to be a wall. I feel sorry for him. If I get enough profit this month, I might buy a new window and hang this one in my apartment.

I know he doesn’t really care. That’s just the way I think about things. I resolve instead to save my money for my big dreams.

The kids outside are shouting and reaching up to me. Their orders hover over their heads as images, shifting a little as the children jump up and down. I can see the old brick of the apartments through the shimmering ice creams: Three strawberry Good Humor bars, a ChocoTaco, two creamcicles, and an ice cream sandwich.

The freezers seem happy to dispense the treats to me, except for the mean one, which wants me to close the window. He doesn’t talk. I just know what he wants. He always wants things closed.

I close him and dispense treats to the kids and they tear off the wrappers and run for the shade, a blur of browns and tans and pastels.

Four kids remain. They can’t afford g-glasses, or their parents don’t believe in the internet or something, so they didn’t order through Uber or Amazon. Instead, they answered to the siren’s call of cheerful music playing out of the loudmouth loudspeaker atop Ms. Truck. It’s music I composed myself, and she (the loudspeaker) thinks it helps her lure in customers on a near-hypnotic level. I don’t know if she’s right, but she likes to encourage my dreams.

It’s hot more times than cold. That’s why I started this business. When I get rich relieving roasted foreheads and parched mouths, I’m going to compose music for Netflix shows and maybe write video game soundtracks. I sell enough that maybe by summer quarter I can cut back my hours and compose more. And maybe then I will buy a walk-in freezer at home and move the lost city there.

The first girl wants a purple Popsicle. She tells me I’m pretty and I thank her. While I wait for my g-glasses to run her card, she tells me she likes the music and she wasn’t going to buy any ice cream except the music made her want it really bad.

The second kid agrees and wants a fudge bar and then both go skipping off together.

The last two kids are burly. The three of us are alone. They stand there silent, glaring, hands in shorts pockets.

“What want?” I stammer. My voice sounds nasal, pinched, forced, stupid. I hate my voice. I write much better, because I have time to think of the words. Music is my real language. I think in music. The sounds line up, complete, all at once. Then all I have to do is refine and perfect them. Like the anthem I’m composing for the lost city.

But music doesn’t translate into words. Not at all. Not ever.

“You retarded?” the tallest one asks.

My eyes flick down to the narrow aluminum shelf below the sill. I feel no shame but suddenly his face is intense, like staring at the sun on an angry day like today.

My answer struggles up like molasses, just as organized. Mere senses and impressions, words mushed. No order, no grammar.

I keep my mouth shut.

Macy lands on my shoulder to help. I see her wings flick in the corner of my eye. They flash pink. Which means I feel ashamed.

I hate when people make me feel ashamed. I won’t let them. The knowledge gives me the strength to look at his face. “Not retard. Want ice cream? Buy or get lost.”

Macy is a five-inch tall praying mantis. She seems to nod at me encouragingly, as if to say, “I’ve got this, Corrine!” before hopping down to the narrow shelf below the window. She cocks her head at the boy, her front claws slowly opening and closing, her wings flicking, now reflecting the yellow of my anger.

I hope she looks threatening. To me she’s just cute.

The boy crosses his arms and the other boy does too. Still avoiding their eyes, I notice g-glasses in both their pockets. They’ve had them all along and took them off on purpose.

“I recording all,” I say. “Go on YouTube. Face ree… uh. Recognition.” On the internet, autism activists will side with me. Ruin their lives.

My eyes are still on Macy. I think the boy smiles. I let my eyes flick up to see.

Suddenly I feel sorry for him. He’s got a black eye. Maybe his dad’s an alcoholic. Maybe his mom hits him. Maybe his brother is abusing him.

Macy’s wings flick cornflower blue. Sadness. I’m sad for him.

“Give me ice cream, retard. And I’m not paying.”

My brain freezes up like the frozen lost city in the third cooler. I don’t know what to do. I have difficulty breathing and think I’m sick. Macy’s wings identify the illness: panic.

“And get rid of that stupid crawly.” The boy takes a swipe at Macy, and she jumps back three inches. She reaches out lightning fast and grabs his finger with her prickly arms. Bites him.

The boy screams and backs up. Macy lets go so he can’t drag her with him.

“Fuck you, you crazy bitch. Nobody sics her bug on me!”

The other boy pulls out a knife and my vision clouds. My chest is caving in. My knees go out and I’m on the floor with my hands over the back of my head. Too much, too much.

I hear a thud against metal and the truck rocks back and forth. There is shouting. I am humming.

Macy is in my face frantically flashing her wings. I reach out and feel the texture of her back, the smooth shiny implant and the veins and grooves in her now-folded wings. Like leaves.

Her touch is like all touches should be, feather light, not heavy and draining like human touches. The sensation calms me. The violent kicking and metal sounds eventually stop crashing through my head, stop filling me with confusing noise. I can see again. I can think again.

“Drive, Ms. Taneka Truck,” I manage to blurt in my horrible voice I hate so much, the voice that caused all this trouble.

The engine starts, and Taneka drives.

![]()

It’s a wobbly ride. The floor is shuffling from side to side. I let her drive, directionless, for a few blocks and then I tell her to pull over.

I get out and examine my boxy, colorful ice cream truck. There’s a flat tire, right rear slashed in multiple places. There are dents and scratches in the siding and through the ice cream pictures.

Macy is on my shoulder and she strokes my hair. I give her a treat and pat Ms. Truck’s side in sympathy. She’s been through far more than I have today.

It’s flaming hot. The cruel pavement is trying to melt my shoes and the cloudless sky feels like it wants to vacuum me into space. The surrounding apartment windows are hundreds of eyes staring at me, boring down, so I rush back into the truck and slam the door.

My face is wet. Macy’s wings tell me I’m upset, sad, crying, reminding me of the emotions my alexithymia hides. I comfort her, pet her. The implant on her back is black and pretty in contrast with her leafy green. I don’t know what I would do without my one constant friend. The first Macy only lived a year but they’re getting better genetics for service animals. This Macy has been with me almost four years.

Macy can sense my pheromones and can see my pulse and perspiration with her keen eyesight to know what I’m feeling. She can also find lost keys when they run off on their own and she tells me when too much time has passed.

And apparently, she makes a good bodyguard.

I suppose I love her. But she would know that better than I do.

It isn’t just tears on my face; there’s sweat from outside. The engine has been off and it’s starting to warm up in here. If any orders come in, I can’t do anything about it. I can’t go anywhere or do anything. And if I can’t sell ice cream, how can I make a living this month? How can I save up or cut hours or write music?

I slide down to the floor; the metal crisscrosses dig into my butt. I wrap my arms around my ears and begin rocking. And humming. I hum the lost city anthem.

I think about calling Mom and my mind spins faster. I don’t want to call Mom. I hate being weak and helpless. I’ve got to find some way to do this myself.

Macy’s feet tickle my arms. I peek out. Orange wings.

It means I’m OS. Overstimulated. I need to calm down. I take a slow, deep breath. I begin to reason with myself. I am not going to get unstuck if I fall apart.

First thing. Sensations. I need to cool off. Then maybe I can call a tow truck.

I need to check on the lost city anyway, to make sure everyone’s alright after all the fuss. I open the freezer and stick my face in. Cold air brushes my skin with prickles and I sigh and relax. Freezer three knows it’s all going to be okay.

The city is carved into the ice. Long ago, the frost formed into round bumps like a volcano cloud. When the twelve first faeliens arrived, two years ago, they hollowed out the shiny crystals and carved in windows and doors, built sparkling staircases and glinting platforms leading to their houses all up the sides. A paradise on this melting Earth.

The only ice cream left in here is a half-eaten pint of Ben & Jerry’s Pony Expresso Bean Soup which the ice had grown around so I couldn’t get it out if I tried. It doesn’t mind feeding the faeliens.

I don’t know what they’re really called. They won’t tell me. I imagine they are either ice fairies or aliens who crashed here on a comet. But I do know global warming has thawed their natural habitats.

They’ve been in this freezer for generations. Two Earth years is enough for them to build families with kids and grandkids. One day, they might outgrow this little case that’s only two-foot cubed. Then I’m not sure where they’ll go.

“Mayor Marschian,” I call softly. He doesn’t mind my voice, unless it’s too loud. He likes my voice, actually.

He opens the door to his palace, a pompous building made of large ice nodules above the pint container. He strides out, regal and grandiose, not skittering at all on his four legs. He holds a long scepter in one bent blue claw. He cocks his head at me inquisitively, his giant eyes iridescent, elongated and pointy like cat glasses. His mandibles quiver and his antennae flick back and forth.

I compliment him on his space clothes. At least I’ve always thought they looked like space clothes. They could be fairy clothes.

He pokes his scepter on the ground, making the cardboard lid vibrate with a papery tap, tap. His back and legs and face are blue like dyed milk.

“Never mind my attire, Corrine! What has been all the ruckus?”

“Got attacked. Bullies.”

Beside me, Macy agrees by wiggling her antennae. She looks like a giant faelien. She could easily be their mother. If she wasn’t well trained, she would try to eat them.

The mayor clacks his mandibles and grumbles. “If we still had our habitat, if we still had our powers, my armies would smite your bullies!”

I shake my head. “No mayor. No vanquishing. Bully scared already.”

Words don’t let me express all my thoughts, but Mayor Marschian understands. I’ve decided he must be telepathic and can hear the music I hear and knows what it means.

His children all rush out to greet me. Their voices are like the chorus of chimes I’ve written into their anthem. They skitter around his feet dancing and cheering and begging me for treats.

“Van-il-wa!” they chant.

I laugh. It’s not dinnertime yet.

An ice cream cone icon pops into my field of vision. My g-glasses are telling me there’s an order two blocks away.

“Got to go. Bye, Mayor.” I close freezer three and remember that Ms. Truck is injured. I sigh and order a tow truck through my g-glasses. It automatically sends them my location. This is going to eat my profits today so I’ll have to sell double to make up tomorrow.

And now a loyal customer is relying on me. I can’t let her down.

Macy flashes a wing. Pale orange, she warns. I need to watch my stress level. Which isn’t helped when I discover the wait time for a tow is one hour.

I glance at the freezers. The compressor isn’t running, but even unpowered, they’ll keep the ice cream solid for a couple of hours. And I can always start the engine if the tow is late. I can walk the two blocks, make the delivery, and be back in time to meet the tow.

I lower my sales radius setting on Uber and Amazon to ensure any new orders are walkable. Then I grab a Double-Stuft Chocolate Sandwich, set Macy on my shoulder, and lock Taneka. I’m not worried about the bullies. They’re far away and not the murdering type. I’m more worried about the heat. Macy reminds me and I go back for a cheerful water bottle to keep us company.

Not sure what I’d do without her.

![]()

Ninety minutes later and the tow still hasn’t arrived. Their site says a high number of overheated engines have delayed them. All the other companies are backed up, too.

I’ve delivered a dozen orders. I’m out of water and outside the pavement is trying to melt me. Inside is a greenhouse. Taneka is very sorry. She can’t help it; the sun is too powerful.

I’ve gone offline. No more orders. No more profits. My dreams seem to be dissolving into hot liquid and running away down the streets in a black mirage. I am tempted to run more orders but Macy won’t let me. She flashes bright orange at me. I’m out of spoons. This day has kicked me in the butt and I need to admit when I’m beaten. So I huddle in defeat in the hot truck, sticking my face in the mean cooler now and then. I take perverse satisfaction in the fact that he can do nothing to stop me.

I check on the third freezer only rarely. I try not to open it too often. The faeliens could reassure and distract me now, but I need to keep them cold or their city will flood.

I peer in through the tiny opening to see how they fare. Their buildings are starting to look a little too shiny. Too wet. Thin puddles are starting to pool up in places.

“You okay, guys?” I whisper.

The Mayor peeks out through his door. He is frowning and shifting uncomfortably. The plastic thermometer reads 35. Too warm. I have let him down. “I fix now!” Standing upright and closing the case, I say, “Ms. Taneka, start engines!”

The air conditioner comes on again and the compressor whirs into action.

“That better?” I say, opening the freezer again and leaning in.

Before he can answer, there is a terrible noise up front, a squeal and a chug. Taneka shudders and stalls.

“What wrong, Ms. Taneka?” Her only answer is a light that blinks on the dash. She’s too old. There is no readout to tell me what’s broke.

I wander up and pat her on the dash. The tow can fix her, I’m sure, but it’s not here yet. I need to check on it myself. Macy is flashing her orange warning but I’ll feel better if I know what’s going on.

I pop the hood latch and leave by the back door, and on my way around the left side, I notice what’s wrong.

The gas cap is pried open. There are knife marks along the edge that match the scratches those boys left on the other side.

They added something to my fuel before I could drive away. Those bullies broke Ms. Taneka.

I smack the side of the truck and quickly regret it, not because it burns my hand, but because Taneka is in enough trouble and doesn’t need to be smacked around just because I’m upset.

I stare into the gaping hole as if I can wish it repaired. I look up and down the street wishing the tow truck would appear and rescue me.

As if in answer, a text icon appears in my vision. I read it. They’re still an hour out.

In another hour, the whole icetropolis will be flooded, destroyed, all their beautiful architecture vanished. And the faeliens will be dead of heat stroke.

There is nothing my mom can do. I don’t know much about engines, but if there is sugar or water or ice cream or pee in the fuel lines, I think a mechanic has to take everything apart.

Poor Taneka.

I glance around at the neighbors. I could plug the compressor in, if anyone would open their door to a crazy retard, and if I had a 100-foot extension cord.

I am wishing I had made Taneka drive me the rest of the way home while she was still running. A ruined wheel can be replaced. A lost city can’t.

Macy is flashing red wings, but I already know it’s too late for me. I glance down to notice I’m chewing my hands, rocking back and forth, humming in a babble under the hot sun. The apartments are staring down at me, judging. I know they can see me. People will never help me now. Now that they know how crazy I am.

Macy hops on the side of the truck door, peering around the corner at me. She wants me to go inside.

It’s baking hot in there, too, but at least it’s dark. There are things I need inside. Things I can’t remember.

Macy will help me. That’s her job.

I rush into the truck, my face covered in tears and snot. I collapse on the narrow metal floor, curled up, and take some solace in how cramped and small it feels. Sweltering. But sheltering.

All I can think about are the faeliens. They must be worse off than me. I have to save them.

Macy is trying to get my attention. I have to save me first.

She carries my meltdown meds in a pouch around her belly. I fumble to open it and she stands stalwart and still. Inside, the pills seem to be all jumping up and down, “Pick me, pick me!”

My mouth is dry but I manage to choke down the most eager one with the help of a softened popsicle from freezer one. Orange sticky coats my chin but I don’t care.

Now Macy is standing on the dashboard, flashing her red, red wings. Yes. The glove box. That’s where I keep them.

I struggle forward, feeling stupid, slow, overwhelmed, and barely able to see. My eyes sting and my skin burns and my head throbs.

In the glove box, I find my eyemask. And earplugs programmed with biofeedback waveforms to cancel outside sound and reinforce calming brainwaves. It’s too hot for the skin squeeze. I leave it there.

It’s almost too hot for the eyemask, too, but I remove my g-glasses and welcome the dark as it hugs my face. I welcome the soft modulated purr from the earplugs. I curl up on the floor and try not to think about the lost city. Save yourself first. Then save them.

I make myself relax.

![]()

When Macy hops on my arm, I know the meds have kicked in and my equipment has worked. I feel better. I have no idea how much time has passed, but the tow still isn’t here. Maybe just a few minutes?

Maybe longer. It’s twilight outside. Getting dark.

Hesitantly, I stand and slowly slide open the door to the lost city.

Water is pooling in the bottom of the freezer. Most of the buildings still cling to the walls, but the roofs of some have melted open, exposing the frightened, overheated faeliens within. They are huddled with their families, scared and dying.

“Mayor Marschian, how I help? What do I do?”

He peers up at me. He knows. He knows the truck is broken and the tow still isn’t here. “Call our people, Corrine. Call our ancestors who brought us across the vast distances.”

I shake my head. I have no idea what he’s talking about. He has always refused to answer my questions about where he comes from.

“Don’t have number,” I mutter. “You call.”

The Mayor taps his scepter on the ice cream lid and the soft sound fills my oversensitive ears. “It is not a number or an email address,” he says. “It is a song. You know it.”

“What,” I say.

I know he means the anthem, which I haven’t officially played for them yet. Just hummed. It’s just a song. A good song, but a song. I don’t believe in magic, and a song can’t call a spaceship.

The Mayor points with his scepter to the top floor of the palace where his family presses their tiny blue faces against the ice trying to keep cool. I know how they feel. If it wouldn’t crush their city, I would be doing the same.

“Save them, Corrine. Call our people. Earth is no longer hospitable for our kind. You have done your best but it is past time we are on our way.”

I glance at the ceiling. The loudspeaker is up there. She has always encouraged me. She sings my songs clear and sweet and you can hear her for blocks around. But it won’t be far enough to reach outer space or fairyland or wherever Marschian’s people come from.

The Mayor is smiling at me. He nods his insectile head.

I walk away. I stare out the windshield down the empty street. Via g-glasses, I upload my rough, unperfected copy of the Ice Palace Lost City Rhapsody to the speaker system.

I touch a button on the dash and loudspeaker sings. It begins with drums, then a tremolo, then chimes, then an orchestra with electronic overtones looping over and under like ice and sugar and snow and chocolate.

Children wander spellbound out of their air-conditioned apartments, leaving doors agape behind them. Their parents come, too. Slowly at first, and then pouring out, attracted to the melody, like they always are.

But this time it’s different. They are laughing. They are dancing. They are not here to buy ice cream. They’re just here to listen, and to learn about the lost city through my song. The way I think about it. Through sounds, not words.

No one would have believed my words.

And they’re filming, too, I realize. Uploading this experience to the internet. The rhapsody is being heard farther away than these mere blocks. It is heard all around the world.

I open the back door and step outside, gazing in awe at my own creation, as if the truck is some kind of shrine surrounded by holy worshippers, and I am just another supplicant, not a priest or prophet at all, not the one who built the temple. Even though I did.

A light arrives. It shines down from someplace above. It seems like it should be too bright. I squint out of habit, but it does not hurt.

There is no sound. It is not a helicopter. They are here. The other faeliens have come to rescue their people from the melting lost city.

Nothing happens. The light hovers over Taneka, and I wait. The crowd waits. The anthem begins again, on loop, and plays through once more while we all just stand there staring.

Macy lands on my arm. Her wings twitch. White. I’m supposed to be someplace. I’m late.

But that isn’t what she means. She is more limited in her ability to communicate than I am. She must mean I’m supposed to do something.

Stupidly, I step up into the truck. I look down at the melting city. The faeliens have gathered now, all atop the pint container, safe from the waters below. Their homes have vanished.

“Deliver us to our people,” the Mayor says in his most commanding voice. I look up at the ceiling. I can’t fly. And I don’t want to go with them. I have a business to run.

“How send you up?” I ask.

And then I know.

“Macy,” I call. She lands on the edge of the freezer.

She would eat them if she weren’t trained. I give her a treat anyway, just in case. Then I detach the med pouch from her abdomen. There is a hook there for adding attachments. I have a larger bag, one that has wanted to help and she feels lonely because I never have use for her. She is large enough to hold all seventy-seven teensy faeliens. It won’t be a comfortable ride, but it will save them.

Macy looks awkward after I attach it, barely flight worthy. But she can still fly. I point at the pint lid. Macy lands and all the faeliens except the Mayor shrink back in fear.

Mayor Marschian strides forward and points his scepter at the bag’s opening.

“Come, my people. We return to the immutable domains at long last.”

All of them, including his wee children, shuffle forward, piling in atop one another. The new pouch welcomes them, like a mother’s hug. They’re like a laundry bag full of blue t-shirts still warm from the dryer.

Hopefully not too warm. “I hope they okay,” I say to the Mayor.

“We have been through difficult times. We are happy finally to go home.” He looks at Macy. Everyone has crammed into the sack except for him. He shakes his head, “We cannot send your companion back from where we’re going,” he says.

I frown and look at Macy, who is cocking her head at me. “I sorry Macy.” Her wings unfurl as cornflower. Sad. I touch my face and my cheek is wet.

She saved my life today. More than once. My only constant friend. “I miss you, girl.”

I wonder then, what she is feeling. If she feels cornflower blue, too. I hope she can find joy in the immutable domains, wherever that is.

Mayor Marschian climbs up her leg and plants himself on her back. He is so tiny there. He holds onto the implant with three legs and two claws and grips his scepter with a spare foot. He’s a blue version of Macy riding her saddle.

“It was good to know you, Corrine. We will tell this tale to our people.”

I nod. “Goodbye, Mayor. Goodbye, faeliens. Goodbye, Macy.”

With that, Macy takes to the air, her wings a messy blur. The colors change through the spectrum, green, red, white, blue.

I follow her out back. All the people gasp and look on as her wings flash in the light, like a summer bug catching prey under a streetlamp. She flies in spirals, up and up, until she disappears into the light’s mysterious source.

And then the light goes out, as if a bulb has given up trying.

Nothing stirs for a while, until I hear a sound like quiet rolling thunder. I realize… it’s clapping.

All up and down the street, people are applauding. They are looking at me. Except their eyes are not boring down or judging or glaring with meanness.

They are smiling. Something I have done has made them happy. Words of music are on their lips. Words of wonder. Words about an ice cream truck and the owner and her amazing music.

They are sharing the videos. They are telling their friends.

I look to Macy to understand how I feel. But Macy is gone. And so is the lost city.

![]()

Unlikely Story

Unlikely Story