Minotaur: An Analysis of the Species

By Sean Robinson

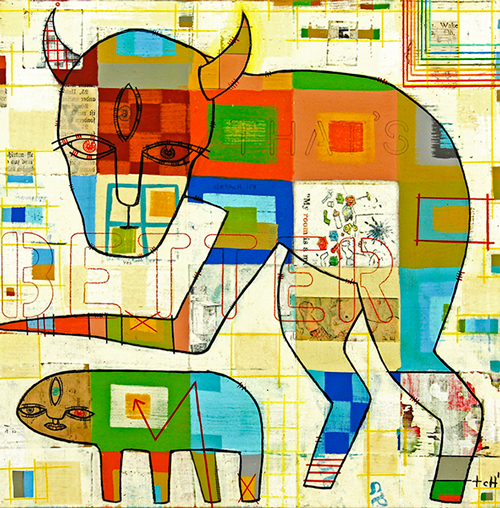

Illustration by Thomas Christopher Haag

Minotaur Makes It All Better by Thomas Christopher Haag

On the Nature of the Minotaur

It is impolite to discuss the parentage of a minotaur. However, science is rarely concerned with propriety and theology is concerned not at all with social graces. A minotaur, the bull-god of the labyrinth, is born in a number of ways, with several consistencies that have been discovered through voluntary self-reporting and questionnaires.

- The mother of a minotaur is always a princess, preferably Cretian. Failing that, Minoan. When all else fails, she usually thinks she’s royalty.

Sixty-seven percent of our respondents identified maternal royal heritage. An additional twenty-one percent stated that they were uncertain of maternal origin. Of the remaining responders, only five percent described royal heritage. One interviewee provided an excellent first-person account which demonstrates this across-the-board consistency:

Momma said she was from Promontory, Utah. I think she was full of shit. But I know wherever she came from, she was royalty. She hopped trains out of Utah like a bat out of hell. Jumping to the next whenever the mood took her. She had the mud of twenty-three states on her boots before she ever met Bull Drucker. He kissed her ’til she couldn’t breathe and left her when the Railroad bosses caught them just outside Detroit and she was too pregnant to jump to the southbound train.

2. The father of a minotaur is always a bull. Sometimes bovine, though often not.

The breakdown of respondents to the paternal-line questions is identical to that of the maternal line. It appears that those who are aware of maternal lineage are also familiar with paternal lineage. From our previous interviewee (identified in interview transcripts as The Route-Bull) it is also clear that resentment often exists between the minotaur and their parents:

What kind of man leaves his woman to have their son in a baggage car? The coalmen were kinder to us than they needed to be. They stayed away until Momma was done, until I was staring up at her with dark eyes. She tucked me away between the barrels of things heading down Texas-way and jumped, leaving me to find my own way.

3. The labyrinth always comes.

In many ways, this last fact plays the dominant factor in the genesis of the minotaur. Though the socio-economic, racial, and geographic origins may be varied and are, according to the study conducted, as varied as the variables at play, in the end, like the modern cuckoo, the minotaur is a brood parasite (possibly symbiote) and is, in the end, always raised by something entirely foreign to its native parents’ species.

However, it is interesting to note that each of the respondents struggled when providing a description of their initial experiences with their labyrinths. In fact, it becomes clear (as described in further sections of this study) that the minotaur and the labyrinth exist in a symbiotic relationship that is not easily defined. As the Route-Bull concluded at the end of his interview:

It was there when Momma wasn’t anymore. It rocked me to sleep with the click-clack of the trains. It was the tracks that people don’t remember, the ones that double back on themselves. It’s kept me safe. It’s magic in middle-America acted out by the engines and the tracks and the train ties.

We were unable to locate the Route-Bull for the agreed-upon second and third portions of the interview. As stated in later sections, it is often the case that the labyrinth prevents access to its minotaur, as other organic systems prevent access to their vital components.

On the Nature of Labyrinths

The word Labyrinth derives from the Greek word labyrinthos, generally associated with the palace-complexes of the Knossos on Crete. Through the interviewing process, each of the minotaurs in our sample has indicated a familiarity with the mythos of King Minos, Daedalus and the construction of a labyrinth. However, this has come through word-of-mouth and the minotaurs’ access to media rather than as a cultural folk-hero or racial memory. As the She-Bull of the Crevasse (Interviewee Number 6) indicates below, historical interpretation and cultural anthropology around the topic may be at odds:

The idea that a labyrinth imprisons us is a fallacy. Does your home imprison you? Does your mate? Or does it provide walls to keep you safe, food to keep your stomach full, warmth to keep the cold at bay? For each of us, there is a labyrinth, whether made of stones or steel, or the azure ice from the cold soul of the earth. If our First Father was born as they say he was, then what was built for him was not a prison. Nothing can contain us.

Respondents to our surveys were asked a number of questions regarding their relationships with their individual labyrinths. As expected, it becomes difficult to have a seemingly inanimate object respond to the formulated questions. Thirty-six percent of respondents indicated that they had been brought to the labyrinth by various conveyances:

I fell. My father packed me into his sledge after seeing what my mother had birthed. I looked at him with the eyes of a doe, as though I’d been born from my mother’s dower-herd. The winter was warm that year and he didn’t realize, until it was too late, that he would die crushed in the cold grip of the ice. I would say that I mourned him, but he watched me fall farther still, watched my labyrinth hold me, watched me crawl into the dark while he cursed me. Let that be a warning.

Evidence of the symbiotic relationship between responders and labyrinths is also remarkable based on the size range reported by the minotaurs in the sample. Some, such as the She-Bull of the Crevasse, maintain a height of 3.42 meters. Others (such as the Stack Beast, Respondent 7) measure approximately 1.94 meters. This appears not to be evidence of sexual dimorphism, but rather a direct relationship between the size of the labyrinth, and the size of the minotaur.

As it grows, I grow. Every chamber, each hall, as the ceilings rise, I rise to meet them. I do not much care what that means. I believe this interview is over.

As with the Route-Bull, researchers were unable to locate the respondent for follow-up interviewing. Researchers indicated that the entrance they’d used previously was no longer present, and reported that the evening campsite was breached by what was described as a “substantial, unknown predator.” No further expeditions were launched in this area.

On the Dietary Predilections of the Minotaur

Myth indicates that the Minoan Minotaur was provided a sacrifice of Athenian youths every seven years. This suggests that the species might be gorge-eaters, falling into dormancy for multiple years. It is also possible that the minotaur follows a life-cycle like that of a cicada, though interviews with Respondent 7 indicate that this is not always the case:

What do you do when you’re hungry, man? Whine about it? No, you go out and order a pizza, you go out for Tapas with your buddies. What do I do? It’s not like I can get delivery. Believe me, I’ve tried. There isn’t a tip big enough in the world to get Pad Thai dropped off in the library’s basement. You tell them to drop it off in the 480s. No one ever gets the joke. [Note: Dewey decimal 480 indicates books on Greek language]

Analysis of the questionnaires indicate that ninety-two percent of respondents identify as carnivores. In some cases, the hypothesis of gorging is accurate, with identification of large consumption followed by periods of dormancy. Two indicated having attempted vegetarianism for “personal reasons,” and a single minotaur identified as “Rocky” responded that they had adopted a vegan lifestyle while living in the Colorado Rockies. It is unclear how these chosen dietary restrictions affect the nature of the species or their relationship with the labyrinth. The Stacks Beast reported that the labyrinth often acts as an enticement for possible prey:

Look. It’s finals week. Is it my fault that some thesis-fried post-grad takes a wrong turn and finds themselves somewhere that shouldn’t exist? They think they’re looking for reference materials for botany, and the stacks start twisting around them. I can hear them muttering to themselves when they realize that the books on either side are 635.93375 and that inside of the twisting paths is me, just waiting. Patient. No one misses a co-ed every once in a while. Man, no one comes looking and if they did, they’d never find anything.

It is worthwhile to note that based on the proposed symbiotic relationship between the environment of a minotaur and its nature, it becomes additionally clear that the preferred diet is that based on homo sapiens at whatever frequency is available. When asked if this observation was accurate, the Stacks Beast responded:

Yes.

Due to the non-disclosure agreement signed by affiliates of this research group, interviewers were unable to alert the institution regarding the unauthorized predator living inside its nationally-ranked library. Nor were they able to report the existence of a labyrinth on the lower floor that extended an indeterminate length of the ivy-league, northern New England institution.

On the Predation of Minotaurs

Due to the hybrid nature of the Minotaur, it’s population is necessarily small. Like some apex predators, the Minotaur cannot abide geographic proximity with its species. This results in no viable breeding population. However, reports indicate that throughout recorded history, where the minotaur has existed, it has faced eradication. In this area, each of the previous interviewees demonstrated a casual, almost Determinist, attitude:

The Route-Bull:

It’ll be a girl who was born in a shotgun house by the train tracks. Her Daddy’ll have worked for one of the railroads and been laid off. She’ll hop her first engine by the time she’s ten and when she finds me, it’ll be because she wanted to know if I was real. She’ll find that I am and that’ll be the end. I won’t be real anymore. She’ll probably be my Momma’s girl.

The She-Bull of the Crevasse:

A man who has yet to prove himself will spend a year making the rope. It will be reindeer hair twisted until it brings him between the ice-teeth of my labyrinth. He’ll follow it, follow me to prove that he is man enough, that he is worthy of whatever girl he wishes and her father will not allow. He will use the reindeer rope around my neck and will drag me from my blue-walled home. He’ll do it because he can, because they tell the story of me in the round-house. He will come because he is the most scared.

Analysis of these responses clearly suggest some similarities in the personal faiths of the minotaur, or perhaps, on the shared experience between each of them. It is possible that this represents a larger predation-prey cycle, or possibly a foundation of belief inherent to the species. The faith (or lack) in the minotaur represents an area of further scholarly exploration, though not one taken up in this report.

In closing, it is perhaps most important to realize that the relationship between minotaur and humanity mirrors the mutually dependent relationship of the minotaur and the labyrinth. One is the product of the other, representing something inherently mutual in our shared nature. It is the response offered by the Stacks Beast that sums it up most poignantly:

The Stacks Beast:

Homecoming Queen, King of the Court, whatever you want to call them. They won’t do it on purpose. They’ll be looking for something else, and find 398.5, modern folklore. He’ll have been drinking cheap beer, she’ll have been pretending the relationship was going to survive freshman year, or that the morning sickness was something it wasn’t. They’ll find me reading Tolstoy or Pliny the Elder. He’ll tell himself that he was the one who did it. But it’ll be her, with the tears in her eyes that does it. It’s okay though. Her kid’ll take my place and the stacks won’t be lonely. That’s all that really matters.

Unlikely Story

Unlikely Story