The Famous Fabre Fly Caper

By M. Bennardo

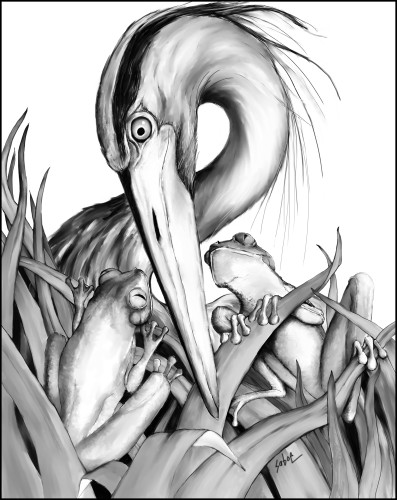

Illustration by Linda Saboe

This is what I wished for, hoc erat in votis: a bit of land, oh, not so very large, but fenced in, to avoid the drawbacks of a public way; an abandoned, barren, sun scorched bit of land, favored by thistles and by wasps and bees. Here, without fear of being troubled by the passersby, I could consult the Ammophila and the Sphex and engage in that difficult conversation whose questions and answers have experiment for their language; here, without distant expeditions that take up my time, without tiring rambles that strain my nerves, I could contrive my plans of attack, lay my ambushes and watch their effects at every hour of the day. Hoc erat in votis. Yes, this was my wish, my dream, always cherished, always vanishing into the mists of the future.

Jean-Henri Fabre, The Life of the Fly

“That’s a queer bird,” said Claud from among the reeds as he cooled his posterior in the mud of the pond bank.

“What bird?” asked Denis. He raised himself slightly on his legs and peered nervously around the pond, for birds were often to be avoided.

“Are you blind?” asked Claud. “Over there — that great hulking black thing.”

Denis shifted his body to look and immediately chirped a cheery laugh. “That’s no bird, you ignoramus. That’s just Fabre.”

And indeed, the “great hulking black thing” was in fact a sharp-featured man just beginning the descent into old age, dressed in a fading black suit, his creased and pocked face peering out in kindly, enthusiastic interest from under a wide-brimmed hat. He carried a glass jar with him, and seemed engrossed in the mud around his feet.

“And just who exactly,” sniffed Claud, whose feelings had been bruised, “is Fabre?”

“He’s the man who owns the house just over there—”

“The house?” asked Claud in distraction. He had quite forgotten there was a house, even though it sat fewer than fifty meters from the water. But one must make allowances with tree frogs — to them, a tree in which to perch and a little pond nearby in which to breed might comprise all the world that is worth thinking about. “Oh yes, the house. But then why haven’t I seen him before now?”

“He spends most days in some dusty old field in back of the house, collecting wasps’ nests and peering into spiders’ holes.”

“Oh, does he…?” murmured Claud, his attention drawn away by a buzzing fly.

“Fabre is a naturalist, I’m told,” continued Denis. “He has studied all sorts of living things, but they say he loves insects most of all. He keeps a great many specimens in cages and jars in the house. In fact, I expect that’s what he’s doing out with that jar at the moment.”

Claud was only half listening, as the fly seemed increasingly likely to land on a nearby sedge leaf. As it swooped lower and lower, Denis’s chirping explanation receded farther and farther into the background — for tree frogs can really only do one thing at a time.

At last, the fly swooped into range, and Claud’s tongue flashed from his lipless mouth, catching the juicy little morsel just as it was about to land. After reeling his tongue back into his mouth, Claud disengaged the fly and pressed it up against his cheek next to another that he had been saving since morning.

“Specimens?” asked Claud, mostly because he was trying to be polite and that was the last word he remembered hearing.

“Bugs and things, I’m told. Loads and loads of them. Spiders seem to be his pet obsession at the moment.”

“And just who is telling you all of this?” asked Claud. Denis somehow always seemed to know everything about everything, at least as concerned the world of the pond and its immediate surroundings. But, of course, the idea of any wider world — even of such quite near places as the little village of Sérignan-du-Comtat, just down the lane, and not to mention any of the vastly distant metropolises of Provence, such as Marseilles or Avignon, each some fifty kilometers away — would have been a shocking concept. “Just where do you get such reliable dispatches of foreign intelligence?”

Now it was Denis’s turn to be offended. He shifted a little, making a show of scanning for flies for a few moments. But, just like most people who seem to know everything, he could not long resist answering any question that was put to him.

“Fabre has a cat,” he said coolly. “The cat stalks the sparrows — whom I suppose even you may know, for they come here to drink every day — and the sparrows taunt the cat. The cat, unable to catch them and being of a weak and spoiled disposition, resorts to sniveling about the greatness and cleverness of her owner, the naturalist Fabre.” Denis shifted a little again, lunging for a fly and missing. “Just how the cat collects her information, I’m sure I don’t know, but she is in the house every day and must know what goes on there.”

Further discussion was silenced as a black and white head with a great orange bill appeared over the tops of the reeds some meters away. The head balanced on the end of a long, snake-like neck, and its large watery eyes inspected the ground with care.

“The heron!” hissed Denis.

She was some distance away yet, but the way the bird slowly scanned the water while stepping delicately through the mud left no question that she was on the hunt.

“And you-know-who will doubtless be creeping along with her.”

“I haven’t got any flies,” said Denis morosely.

Claud harrumphed. “Then let’s hope we aren’t found out.” With that, both frogs dived into the pond, sinking down to the murky bottom where they could cover themselves in the suspended muck of the bed. Above them, the surface of the pond vibrated momentarily with two radiating circles of ripples, but soon enough all was quiet again.

![]() A frog can be very still when he wants to be. And at that moment, with the heron searching and hunting above them, Claud and Denis wanted to be as still as stones at the bottom of a well. And if there had only been the heron to worry about, they would doubtless have escaped detection. But this heron, who went by the name Aurélie, found that it was to her profit if she did not work alone.

A frog can be very still when he wants to be. And at that moment, with the heron searching and hunting above them, Claud and Denis wanted to be as still as stones at the bottom of a well. And if there had only been the heron to worry about, they would doubtless have escaped detection. But this heron, who went by the name Aurélie, found that it was to her profit if she did not work alone.

And so it was with a sinking feeling in his stomach that Claud felt a webby hand press against his back. Before he even turned around, he knew he’d find one of the enormous marsh frogs — more than four times his own size — giving him the hardest stare an animal can when his eyes are on entirely opposite sides of his head. Overhead, a large shadow moving from side to side proved that Aurélie waited above.

“Well, my boy,” said the marsh frog, a giant bubble resting against the roof of his mouth as he spoke. “Have you got your payment for the Syndicate?”

Claud sighed. There was nothing to do but cooperate. If he refused, a single croak from the marsh frog would tell the heron to strike. In fact, there was little doubt that Aurélie would take any excuse whatsoever to snap him up. Sullenly, Claud disgorged one of the flies he had been keeping against his cheek and watched in fury as the marsh frog gobbled it up.

“Timely payment,” puffed the marsh frog. “And a juicy fly, at that. This is a good mark for you, my boy. The Syndicate could use a few more decent tree frogs like you.”

Claud only glared back, hatred burning in his elliptical pupils.

“Now what about this other fellow?” asked the marsh frog, laying its hand on Denis next.

Denis was hopelessly distraught as he emerged from his hiding place. He trembled before the marsh frog, the heron’s shadow cold and dark above him. He could even make out two thick stick-like legs jutting down through the murky water, and the spidery spread of clawed toes.

“I haven’t gotten any yet today,” Denis whispered. “Give me a little more time, please!”

The marsh frog eyed Denis critically. “You look fat enough for a tree frog, eh?” He poked Denis in the ribs with his hand. “You haven’t been snacking on bugs that should rightfully belong to the Syndicate, have you?”

Denis turned pale and shook his head feebly.

“Just lazy then, eh? I’m afraid this is a bad mark for you, my boy. In fact, we may have to consider you an unproductive drain on Syndicate resources.” The marsh frog made an airy, imperious gesture, as though to include the entire pond among these so-called Syndicate resources.

“No, please!”

Claud cringed. He expected at any moment that the great bill would flash down and send Denis wriggling down the hateful bird’s endless esophagus. Such was the way of the Syndicate — its stooges grew fat on the “payments” they extracted from every frog and toad in the pond, and the heron got an easy meal whenever some unfortunate like Denis failed to keep up with the extortion.

“Wait,” said Claud. “I’ll pay for him.” He disgorged the fly he’d been keeping since morning, leaving him with nothing to show for the day. But this wouldn’t be Claud’s first hungry night since that overgrown natterjack bully Grégoire had conceived of the Syndicate racket as a way to stuff his belly without doing any work himself.

The marsh frog eyed the fly critically — it was a small thing, and badly damaged from being carried around all day. But finally he sniffed and sucked it into his mouth as well. “Boss Grégoire will hardly be pleased with this one,” he said. Then he turned to Denis. “Your friend has got you off the hook this time. But don’t expect to make this a habit — every frog has to produce his own payment.”

With that, the marsh frog swam away, its long legs taking it deep into the pond with a couple graceful kicks. The shadow lifted a moment later as Aurélie followed after. Claud and Denis settled back down into the muck of the pond, trembling at their close call.

Finally, Claud asked, “What kind of specimens did you say Fabre keeps in his house?”

“Mostly spiders at the moment,” said Denis quietly.

“And how many did you say he had?”

“Loads and loads,” croaked Denis.

“And,” asked Claud after a few moments had passed, “what exactly does he feed them?”

![]() Claud was not a bad frog by any means, and he was certainly not a mean one. But ever since the pond had been taken over by the Syndicate, with its blatant corruption and coercion, there had been some erosion in the morals of the animals suffering under its rule. So when Claud speculated on the insect riches that must be kept in Fabre’s house, he felt no twinge of conscience if his plans evolved along the same lines as those of a criminal plotting a burglary. He was simply doing what was needed to survive.

Claud was not a bad frog by any means, and he was certainly not a mean one. But ever since the pond had been taken over by the Syndicate, with its blatant corruption and coercion, there had been some erosion in the morals of the animals suffering under its rule. So when Claud speculated on the insect riches that must be kept in Fabre’s house, he felt no twinge of conscience if his plans evolved along the same lines as those of a criminal plotting a burglary. He was simply doing what was needed to survive.

Late that night, Claud and Denis descended from their tree to see what they could discover at the house. The spider specimens themselves weren’t the target of the investigation, but rather the vast store of flies Claud had convinced himself Fabre must be keeping for their food.

The pond was alive with chirping and croaking as Claud and Denis crept across the grass of the lawn. In fact, on spring nights such as this one, the pond and the surrounding wetlands were home to a veritable cacophony of chirps, croaks, and peeps reverberating across the surrounding countryside.

For a long time, the house seemed to stay the same size — it was simply “big” and “far away.” But after a few moments, it looked distinctly closer, and they could make out the outline of the piled stones of the walls and the misshapen outline of the chimney. Lamplight seeped out from the crack under the door and from behind the curtains. Somewhere inside, Fabre was inspecting one of his specimens, or devising an ingenious experiment, or writing one of his famous Souvenirs entomologiques.

Claud had interviewed the sparrows earlier that day, and they had told him where to expect the spider cages — boxy enclosures that sat out back behind the house, covered in netting to keep the inmates in. But the sparrows had never seen anything looking like a container of flies, and so Claud suspected it must be kept inside. The first task, then, was to find a way into the house.

Generally speaking, tree frogs have very little to do with houses. Therefore, Claud’s plan had been very fuzzy on the matter of ingress. He expected they would simply climb up to some hole or crack, and squirm through until they found themselves in the house. After all, garden walls and tree trunks always abounded in holes and cracks. Why should houses be any different?

After some hours and a great deal of fruitless exploration, Claud finally managed to find a sufficiently large crack under the front door, squeezing into a gap between boards. Denis followed and at last they were in Fabre’s house.

By this time, the household had gone to bed. All the lamps were extinguished, and everything was silent — save, of course, for the chorus of chirps and croaks rising up from the pond and the wet earth all around the house.

The requirements of frog biology usually make them very timid explorers, except when water is present. You will not ordinarily find two tree frogs systematically searching the rooms of a house, hopping along the dusty flagstones and using the soft sticky pads on their hands and feet to climb up every table leg. However, if you had been a silent, hidden observer in the shadowy corners of Harmas (which was the name for Jean-Henri Fabre’s house in Provence) on this particular night in May of 1883, then that is exactly what you would have seen if you had looked close enough.

It was Claud, at last, who found the treasure they sought. It took the form of a large box, about fifteen centimeters in every direction, made of a light wood frame covered tightly with translucent parchment paper. Claud could hear the flies buzzing inside, their wings vibrating against the parchment walls. How many flies, he wondered. A hundred? Two hundred? A thousand or more could easily have fit in that space, though Claud did not necessarily expect the entire box to be full.

“It’s up here,” chirped Claud. He had tried calling to Denis as softly as he could, but frogs are not known to be great judges of acoustics.

“You found it?” chirped Denis.

“Yes! Come look!”

This idle and unwise chirping went on for quite a while as Claud and Denis excitedly inspected their find. There did seem to be no doubt that the box was full of an extraordinary number of flies — enough to pay off the Syndicate for the rest of the spring and summer, most likely. If they could only somehow get possession of the insects inside the box, they might rest easy for the rest of the year.

It’s perhaps for the best they were interrupted at that point by a loud banging and grousing from the next room, or else they might have tried to open the box right away. But instead, they both jumped six inches at the sounds, and suddenly realized they had foolishly woken up the people in the house.

“I can hear them, I tell you!” growled a man’s voice, which we may take for that of Jean-Henri, the naturalist himself.

“Darling, please,” said a woman’s voice, which must have belonged to Marie-Césarine, his wife. “You’re just over-tired and agitated.”

“I am over-tired and agitated,” grumbled Jean-Henri again, “on account of this incessant chirping night after night. But I can hear them in the house, nonetheless!”

Denis gulped. “We’d better hop,” he said, “and come back for the box another night.”

“Ah ha!” shouted Jean-Henri as he stumbled into the room, his face lit by the flickering light of a taper. “You hear that?” He advanced upon the frogs and promptly barked his shins against a chair in the darkness.

“Indeed!” chirped Claud, and both frogs jumped down off the table and wriggled back under the door. Only Fabre’s cat, who had quietly slinked into the room along with her master, remained to watch the long, fruitless search that followed until Fabre’s exasperation gave way at last to exhaustion.

By the next day, Claud had realized his plans regarding the fly box required further development. Reflection had revealed to him the disaster that would have followed if they had opened the box while still in Fabre’s house. It seemed what was called for was to take the box out of Fabre’s house, and to keep it in a place where Claud and Denis could harvest its riches at ease, one fly at a time.

Human readers, with the advantage of human intellects, will instantly point out a host of problems with this plan. How could a frog ever manage to transport such a monstrous piece of furniture anywhere? Where could it be hidden so Claud and Denis could get at it when they liked, but the stooges of the Syndicate could not? And, of course, how were the flies to be kept alive once they were taken away from the succoring hand of Fabre, and his eye-droppers of sugar solution?

Claud, however, did not have a human intellect. He had a frog intellect, and in true frog fashion he thought it sufficient to consider only the first problem that occurred to him — that of getting the box out of Fabre’s house. All the same, it was half a day of thinking before he had any kind of solution at all.

“I keep thinking it over,” Claud finally said to Denis, about mid-afternoon, “and I don’t see any other alternative. We’ll have to cut in the heron on the job.”

To Denis, this sentence was full of so many horrors that he hardly knew how to respond. Phrases like “cut in” and “the job” carried with them an unmistakable tang of criminality — a tang that had increasingly peppered Claud’s language of late. And then, this horrible reference to the heron! Denis looked furtively around, as if to be sure the uttering of the words had not conjured the monster herself, but Claud was already forging ahead.

“Aurélie is the only creature I can think of who would have any hope of carrying that box away intact.” Claud tapped his front leg pensively on the lily pad on which he was resting. “But why would she ever consent to help us?”

The minds of animals do not run in many channels, and it was not long before Claud determined food must be the enticement for Aurélie. The flies would not appeal to her, of course. But perhaps the spiders would be juicy enough?

Claud impulsively called to one of the sparrows drinking at the pond not far away. “Hey, sparrow! Is Aurélie somewhere about here today?”

“She’s on the other side of the pond,” answered the sparrow. “You’ve no need to worry for now.”

“I wonder if you’d carry a message to her for me?” asked Claud. “In particular, I wonder if you’d ask her if she would be interested in making a meal out of a lot of fat spiders? Perhaps she’s seen the ones I mean — the spiders in the boxes outside Fabre’s house.”

After getting over the shock of a frog asking to send a message to the heron, the sparrow got up and flew over to Aurélie to put the question to her. It was a novel situation, and he wanted to see what would come of it. A moment later, the sparrow was flying back with the response, and perched on a rush to deliver it.

“She says spiders aren’t ordinarily in her line, but that she would have eaten the ones in the boxes long ago if the netting hadn’t gotten in the way.”

Claud croaked in approval. “Excellent, excellent.”

But before he could continue, the sparrow interrupted him. “Begging your pardon, but I can see the heron leaping up into the sky right now. I think she intends to come over here and continue the interview in person.”

“More like she intends to eat us,” said Denis in despair.

“Yes, I’m not sure a personal interview would be wise…” Claud looked about and then pointed at a little rock in the middle of the pond on which a couple of small turtles were sunning themselves. “When Aurélie arrives, tell her that we will remove the netting for her if she consents to carry out a box from inside the house for us. Then meet us over by that rock to give us her answer.”

At that, Claud and Denis disappeared into the water. By the time they surfaced over by the rock, they could see Aurélie pacing around the bank of the pond where they had been sitting. She looked a little perplexed to find there were no frogs waiting for her, but a moment later the sparrow was winging over with another message. This time he alighted on the shell of a turtle.

“She’s agreeable to the idea, so long as it’s not too big of a box, and so long as the box doesn’t contain anything that she should like better than spiders, and so long as the windows are open wide enough to let her in.”

Claud waved his arm. “Yes, yes, it’s just a box of flies, which I doubt she would have any interest in. Tell her that Denis and I will creep inside the house tonight and make sure the windows are open, and then once she has taken out the box we will remove the netting from the spider cages.”

“Begging your pardon—” said the sparrow again.

“Go on, go on,” said Claud. “We’ll wait for the answer.”

But no sooner had he finished chirping, then Aurélie herself landed heavily in the muck by the rock, her wings outstretched to break her fall from the sky. The turtles instantly slipped away into the water, and the sparrow had to jump quickly to avoid getting dunked. In an instant, only the two frogs remained. Before they could move a muscle, Aurélie’s bill hovered over top of them, as if ready to make a meal out of both frogs at once.

“I roost at night,” squawked Aurélie in her ragged heron’s screech. “And the windows will be locked. Either we will do it now, or not at all.”

Claud gulped, a shiver running through his whole little body. Denis seemed ready to pass out. “Now then, of course,” Claud whispered.

Aurélie hung over them a moment longer, and then nodded her head. “And where would you like this box placed?”

“I suppose our tree would be the best place…” stammered Claud.

“Then quickly up to the house while everyone is napping!” And with that, Aurélie flapped heavily up again to take her position on the lawn outside the window. A moment later, when Claud and Denis had regained their composure, they slipped into the water and swam off in the same direction.

The Famous Fabre Fly Caper (as it would later be called by generations of admiring polliwogs) was destined to be remembered more for its audacity and for occasional flashes of ingenious improvisation than for any craftsmanship that went into its planning or execution. After all, it is not merely a matter of the difference in species that the name of Claud the tree frog is not often mentioned in the company of others such as James Moriarty, A.J. Raffles, or Arsene Lupin. The truth is that it is difficult to imagine any of those great criminals allowing one of their projects to be engulfed by such a whirlwind of chaos as that in which Claud and Denis were soon to find themselves.

The unraveling of the thin plan began almost as soon as Claud and Denis squeezed under the front door. The inside of Fabre’s house looked considerably different in the afternoon light — the rooms seemed smaller, for one thing, but also more perilous. If the frogs should be heard or seen on this excursion, they were far more likely to be caught or killed.

And, in fact, Claud and Denis were seen, almost as soon as they entered the house. It was the cat, lounging on a chair in a ray of sunlight, who happened to notice them. This was an extraordinary coincidence, for the cat had just been thinking about the two little frogs who had been in the house the night before. She had been dreaming about how happy it would make her master to receive the little gift of their headless bodies — for he had certainly seemed very interested in the creatures.

And so the cat was dreaming about how cunningly she would stalk and catch those two frogs down by the pond. She often had such dreams about little animals that came around the house — mice and sparrows and so on — and very often they amounted to nothing more than a pleasant afternoon’s musing. It was cold and wet down by the pond, and it was full of quacking ducks and hissing geese, and little animals had the annoying habit of jumping or scurrying or flying away at the last moment. Much better to do her stalking and killing in her mind, so thought the cat, where those unpleasant realities need not intrude.

When Claud and Denis hopped out from under the front door, the cat had just got to the part of her dream where she was solemnly laying their decapitated bodies at Fabre’s feet, ready to receive the praise and treats she knew would be her reward. She was bewildered for a moment by the sudden appearance of the subjects of her dream in the flesh, and at first she was frozen in a strange state of shock. But then a shiver went down her spine as instinct took hold, and suddenly her eyes snapped wide open and her claws slipped out of their sheaths.

For their part, the two frogs knew nothing of the cat until she had flown over their heads and skidded into a pile of boots next to the door. Claud had been distracted, thinking about the window and how they might manage to open it wide enough to allow the heron inside. Denis had simply been realizing, little by little, how much he disliked being there at all. But as the boots toppled over and the cat emerged from the disordered pile, they were both snapped violently back into the moment.

Claud and Denis found themselves huddled under a nearby chair, hurried there by instinct before they had even really comprehended the situation. Likewise, instinct ordered the cat to once again hurl herself at her prey — this time colliding with the chair and sending it spinning across the floor. At this, Claud and Denis hopped behind a pile of books which was, in short order, tumbled down by another yowling leap.

As instinct shuttled the frogs and their pursuer from one shelter to another, Claud’s little intellect began to assert itself again. The problem he had been concerned with — how to open the window wider on its hinge — merged in his brain with the problem at hand, and suddenly Claud had one of those flashes of brilliant insight.

“Quick,” he hissed to Denis. “Behind the bookcase!” And in an instant, the two frogs were wriggling into the crack behind a small bookcase which sat against the wall under the window. The cat’s paw reached deep into the crack behind them, swatting and swiping, but she soon found herself pressed flat up against the side of the bookcase, frogs just out of reach and unable to stretch any farther.

Once her blood was up, the cat was not the sort of creature to be so easily deterred. If she couldn’t get the frogs from one side, she would soon try reaching from the other, or down from the top. If those tactics failed, she would push at the crack until it parted and she could force herself inside.

Claud and Denis, however, did not wait for those developments. Instead, they pressed the sticky pads of their hands and feet to the wall and began to climb up behind the bookcase, up and out, until they reached the windowsill above. And no sooner had they crawled over the sill and onto the windowpanes than they were confronted with the searching eye of the heron — yellow and limpid — staring back through the window and into the house.

Aurélie was in fact trying to see what was going on inside the house. She had started to wonder if the frogs had met with some accident, and found herself regretting that she had not eaten them when she had the chance. For a moment, she was taken aback by their appearance clinging to the other side of the window before her — but it was only a moment before she realized this was a second opportunity to make a good meal.

Of course, if there were any hope that the frogs could actually open the window, she might play along long enough to get those spiders as well… But as things stood, she didn’t see how such tiny animals could ever open the window any wider than it already stood. This flaw in the plan should have been evident from the beginning. Now that it had become clear to Aurélie, she considered the deal well and off.

Stepping delicately to the side, Aurélie tilted her head and opened her bill. Daintily extending it into the crack of the window, she blindly groped, searching for the frogs and ready to snap shut when she should find them.

But it was at that moment the cat noticed the frogs had climbed out from behind the bookcase. Coiling herself for a leap, she let out a furious yowl and launched herself over the bookcase at the window. Mid-air, she caught sight of the sharp heron’s bill tapping its way along the windowpane. Twisting herself in surprise, she struck the window with her back and proceeded to tumble out into open space. Aurélie jumped back with her feathers all disordered. The window itself sprang wide open at the force of the impact, and Claud and Denis could only hold on as tight as they could.

Denis, who was always less finely constituted than Claud, actually succumbed momentarily to the bliss of unconsciousness. All of the stress of the moment melted away, and he floated on a cushion of peaceful ignorance. An eternity seemed to pass — a wonderful eternity free of cats and herons, free in fact from every bodily care.

In reality, the eternity passed in a single second, and when Denis returned to awareness he found himself still clinging by reflex to the windowpane next to Claud — but now with Aurélie perched on the windowsill behind him, wings fluffed out over her back and neck extended as she squawked at the startled cat below. The cat, for her part, was so dismayed and demoralized by these unexpected developments that she sped off around the house as soon as she found her feet again.

Cognizant that the situation had changed again, Aurélie stepped lightly from the windowsill and floated to the table with the box on it. “Yes,” chirped Claud. “That’s the box! Now quickly, fly it out the window so we can drop to the ground and get to those spider boxes before the cat returns to trap us.”

“In good time, in good time,” squawked Aurélie. She poked at the box gingerly with her bill, tipping and tilting it on the table. “First we shall find out what is in here.”

“It’s flies!”

“So you say… But how do I know it isn’t really something better?” Aurélie snaked her neck back towards the window as she asked the question. Clearly she was a creature so used to deceit and double-crosses that she could hardly imagine Claud might be telling the truth.

“Hold on there!” came another voice — a deep and throaty croak. It bore with it such an air of command, everyone really did stop to listen. “I shall open the box, for it is mine now. Bring it down to me here, Aurélie.”

The new arrival was Grégoire, the natterjack toad boss of the Syndicate, who had dug his way under the door just moments earlier. He was accompanied by practically every marsh frog from the pond. For what had happened was this: moments after Claud and Denis left for the house, the sparrows started spreading a lot of sparrow gossip about a great house full of thousands of flies. Grégoire had woken from a nap to the unpleasant news that a great mass of insects were about to bypass the Syndicate altogether, and he had instantly mobilized his strongest enforcers. The rest of the marsh frogs had then followed after, afraid that by hanging behind they would lose their share of the spoils.

The front room of Fabre’s house, now full of frogs and with a heron perched on the tabletop, looked more like a pond than the pond itself at that moment. The cat, meanwhile, could be heard yowling from the other side of the front door, her paw reaching up through the hole that Grégoire and the marsh frogs had dug to get in.

“All we need now is for Fabre himself to show up as well.” So chirped Claud, despair in his voice, as he watched Aurélie drive her bill down into the parchment covering of the box, releasing the startled flies in a buzzing cloud.

“I’m told he naps on the back porch in a hammock at this hour,” answered Denis. “So we might as well take this moment to slip away…”

But Claud felt a sudden surging in his breast as another inspiration hit him. “No, my brother!” he said. “Sing as loud as and as fast as you can! Sing for all you are worth!”

The rest of the tale is not long in the telling. Claud and Denis did sing for all they were worth, their throats vibrating heroically as they sent their high piercing calls out into the sunny afternoon.

So insistent where they in their singing that eventually they achieved what the squawks of Aurélie and the clatter of the cat could not — they woke the naturalist himself, Jean-Henri Fabre, from his afternoon nap. Weeks of being tormented every night by the chorus of chirps and croaks coming from the pond had left Fabre’s nerves finely tuned to the calls of frogs. He awoke in a rage, for it seemed the frogs would not even let him nap during the day.

Claud and Denis kept singing until they saw Fabre burst into the house from a back entrance. He was a terrible sight with his collar unbuttoned, his hair in disarray, a broom in his hands that he wielded like a battleaxe. But berserker that he was, the sight which met his eyes in the front room stopped him in his tracks.

Marsh frogs covered the flagstones, hopping and crawling after hundreds of flies who filled the air, landing here and there as they searched for the windows. Meanwhile, the cat was raising an unholy racket from outside the front door. But most startling of all was the grey heron standing on the table, picking apart the parchment fly box with its bill as a natterjack toad hopped uselessly again and again on the floor far below.

“My God,” whispered Fabre, pressing a hand to his forehead but finding no sign of fever.

The heron was the first to see how things stood. The box truly contained nothing but flies, and the room was hemmed in now by man and cat. Sweeping her head around the entire room, Aurélie could see there was no escape for any of the marsh frogs anymore. Without the climbing ability of the tree frogs, they would never reach the windows, and the only other exits were now both closed off. The Syndicate didn’t seem likely to outlast the day.

Cutting her losses, Aurélie jumped down from the table and plucked Grégoire from the floor with a sharp stab of her bill. Tilting her head back, she severed her ties with the Syndicate forever. Then leaping up to the window, she balanced a precarious moment on the sill before leaping again, taking wing, and flying away from the coming scene of carnage.

Claud and Denis, meanwhile, took the appearance of Fabre as their cue to release their grips on the window, dropping lightly to the wet grass below. As they crept away towards the pond, they could hear terrible noises and curses coming from the house as Fabre relieved himself of his frustration against the frogs that had robbed him of sleep for almost a month. None of the marsh frogs ever returned to the pond, and though Claud and Denis never learned exactly what their fate had been, it is a well-known fact in Provence that they make an excellent dish when breaded and fried in butter with garlic and parsley.

Though Claud and Denis never tasted any of Fabre’s flies, they returned to a pond where the oppressive heel of the Syndicate had been forever lifted. Aurélie had given up on amphibian alliances, so they had only to contend with the normal dangers of life in the countryside. Being clever frogs who looked out for each other’s welfare, this ensured that Claud and Denis lived many happy years among their friends.

For his part, Fabre did find his pond much quieter after the strange events of that day, and soon his nights were restful and refreshing again. Even into his old age, thirty years later, he often thought (with some embarrassment) that the marsh frog massacre had been responsible for the change.

But Fabre, of course, could never know that on moist May nights, when the tree frogs were apt to sing their loudest, there were in fact two grateful agents creeping from tree to tree on his behalf, whispering to their brothers and sisters, and to their nephews and nieces: “Softly, softly now. We mustn’t disturb old Fabre, for we owe to him still our lives and liberty.”

In front of the house is a large pond, fed by the aqueduct that supplies the village pumps with water. Here, from half a mile and more around, come the frogs and toads in the lovers’ season. The natterjack, sometimes as large as a plate, with a narrow stripe of yellow down his back, makes his appointments here to take his bath; when the evening twilight falls, we see hopping along the edge the midwife toad, the male, who carries a cluster of eggs, the size of peppercorns, wrapped round his hindlegs… Lastly, when not croaking amid the foliage, the tree frogs indulge in the most graceful dives. And so, in May, as soon as it is dark, the pond becomes a deafening orchestra: it is impossible to talk at table, impossible to sleep. We had to remedy this by means perhaps a little too rigorous. What could we do? He who tries to sleep and cannot needs becomes ruthless.

Jean-Henri Fabre, The Life of the Fly

Unlikely Story

Unlikely Story