The Librarian’s Dilemma

By E. Saxey

Illustration by Liam Quin

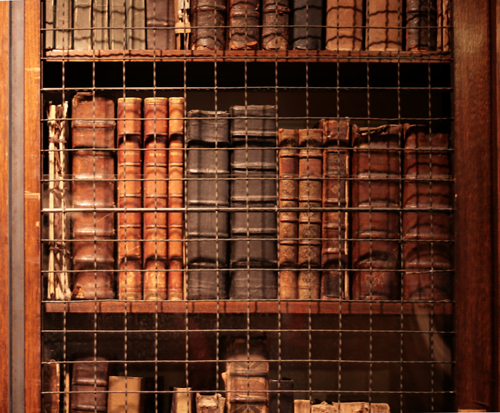

Caged Books by Liam Quin

Jas’s job was to bring libraries into the 21st century. St Simon’s library hadn’t left the 17th, yet.

Jas stood in a University quad, surrounded by stone buildings. In the centre was a huge yew whose branches brushed the walls. The wooden library door, ahead, was studded with nails.

The house Jas shared with his mother in Bradford would have fitted comfortably into this quad. Jas felt his principles — the anti-elitist, democratic ones that drew him to work in libraries — should have soured the sight. But they didn’t. He felt out of place (too brown, too poor, too queer) but was still attracted.

The oak door opened. An older woman appeared in its shadow, straight-backed in dark clothes that swung about her like robes.

“Jaswinder? I’m the librarian for the Harrad Collection. You’ve brought a lot of luggage.”

Jas was smuggling the future, in big suitcases. Digitisation equipment: expensive, and unique, and terribly heavy. They’d been hell to drag around on the long train journey (although had probably done wonders for his developing arm muscles). The librarian hasn’t asked for them, his boss had said. But you can change her mind. Just don’t tell her you brought them with you. “I wasn’t sure what the weather would be like,” Jas said.

“I’ll send Fred to help.”

She slipped back inside, and from the same door rocketed a figure in a suit, thin as a stick with thick-framed glasses and a mane of hair tossing around. “Hand ’em over. I’m stronger than I look.” A Scots accent. “I do all the shelving. Up and down the stairs, too — no lifts, the place is too old.” He grabbed a case, swung it over his shoulder, staggered a little. “Follow me.”

Up a stone staircase, into a room overlooking the quad. The yew tree pressed its fingers on the leaded glass window.

“Do I sleep here?”

“Yep. Student rooms. I’m down the corridor.”

“Aren’t you a librarian?”

“God, no. Who’d want to do that?”

“I do.” His holiday job was a decent start, but Jas planned (when he’d finished his degree) to get properly chartered.

“You’re young. You’ll grow out of it.”

Fred lead Jas back to the library. A dim room, as long as one side of the huge quad. When the door opened, a knife of light stabbed across the floorboards. Tweedy readers clustered around the windows. Academics were strange. Any sane person would take a book outside, sit under the tree.

The librarian looked up from her desk near the door, shook back her bobbed grey hair.

“Jas. Call me Moira. Now, we have you for eight weeks?”

“Yes.” Or longer, if they need you, Michelle-the-boss had said.

“You’re going to tag our rare books, and connect each book to our catalogue record. You’ve had experience?”

“I tagged the incunabula in the founders’ library in Lampeter.” A miserable wet fortnight in Wales, but useful for the CV.

Moira laid a book on her desk. “Show me.”

Jas eyed the book, conscious of being auditioned. Nice leather binding, useful crescent-moon gap between the sewn pages and the spine. He took from his bag a small plastic box and a slim long tool, like a sparkler. Talk them through it, Michelle reminded him.

“So these are the seeds.” The box was full of flat beads, like white lentils. “And I pick one up…”

Dipping the sparkler in the box, giving it a theatrical stir, then tapping to dislodge all but one seed.

“Then we…” He slid the sparkler into the spine-gap of the book. Good: no knots of glue, no tearing threads. You wanted the invisible worm, from Blake’s poem, to wriggle into the book and hide the seed there, in the spine or the cover. The benevolent reader would never notice, the malevolent reader would never be able to find the seed and remove it.

“And now you can never lose it.” It was part of the sales patter, but heartfelt. In a traditional library books got lost, not just in a prosaic sense (like lost keys) but in a profound way (like lost souls) — misplaced, they became inert, never again to be useful.

This was a great time for a quick demonstration. Find an excuse, Michelle had said. It’ll hook them.

“Can I show you…” Jas moved around the room, sprinkling seeds at different heights on the shelves. (They were fiddly, but you couldn’t, ipso facto, lose them.)

This was the fun part. “Now, if you want to find something…”

Jas held his device up to the room. The screen showed dots of light sprinkled all around. Constellations. Jas knew why it worked: because librarians thought of themselves as being Gods of a miniature cosmos.

“Each light is a book. And when you know which book you want…” Jas turned off all the seed-lights except for the one he’d just installed. A single light remained, the star over Bethlehem.

“Hmm. I suppose it could be useful,” said the librarian.

Jas felt his smile congeal on his face.

![]()

“OK, let’s do philosophers,” said Fred.

“Plato.”

“Ooh, a toughie. Ockham! William of Ockham. Your turn.”

“Morris. William Morris.”

“Sartre!”

At Moira’s instruction, Fred was helping Jas to seed the books. He was beaky, frenzied, seemed likely to jab a seed tool straight through a book cover. “I’m only working in this library until I get a post-doc job,” he’d announced. Jas resented this slur on the profession, but Fred did help to pass the time with whispered word games. Without Fred, it would have been dull work; Jas never read the books he seeded, to avoid getting sucked in.

By lunch on the first day, they’d seeded a huge stack of texts.

“We need the catalogue,” Jas whispered. “To match the seeds to records. How do I access it?”

Fred pointed to a beige terminal.

Jas read a peeling sticker announcing it had been inspected for safety. “Ten years ago?”

“Well, it passed!” Fred said. “What more do you want?”

When consulted, Moira searched under her desk and dragged out a laptop, maybe only five years old. “Don’t take it out of the library.”

It was ridiculously slow. The ancient kit was inexplicable, given that St Simon’s was so well endowed. The library catalogue wasn’t complex, you could run it on anything. Jas could load it on his phone, for goodness’ sake.

After an hour of wrestling with the ancient laptop, he did just that, and the work went so much quicker he nearly cried with relief. He kept the laptop open in case anyone was watching.

![]()

On the dot of five o’clock Fred stood and clapped his hands. Every tweedy reader looked up, and half of them closed their books and donned their jackets. Fred the pied piper led them towards a pub on the seafront.

“Why do you want to be a librarian, then?” Fred asked Jas as they walked. “Isn’t it a wee bit boring?”

Jas wondered if he was being tested. “There are radical librarians.”

“Really?”

“Yeah, fighting restrictions. Freeing information.” Jas admired them for all those things. What stole his heart was also the multicoloured hair, the facial piercings, and the fact that half of them seemed to be trans or queer. “Mostly in America,” he admitted.

“If you say so. I’ll get the drinks in. Connell, tell Jas about your research!”

Connell was a squat black professor from Los Angeles. He nodded his bald head sharply at Jas. “Trauma! War, civil conflict, interpersonal violence.”

“Oh. Goodness.”

One by one, the other researchers named their expertise.

“Italian Fascism.”

“Madness. Sorry, I wouldn’t say ‘madness’ normally, of course. But I’m eighteenth century, it’s all madness, lunacy, all that outdated terminology.”

“Medical ethics. Well, mostly when it goes wrong.” That was a woman from Sweden.

“I suppose you could say… the occult?” A younger man wearing a pentagram necklace.

“Mass graves.”

There was nobody else to speak. Say something! thought Jas. Anything! “Nazis?”

“Not really.”

With a clunk, Fred set down his tray of pints.

Ritual grumbling commenced. Jas knew it had all been said before, because people took up one another’s refrains.

“If I could take books back to my room…”

“And you’re only working on early 20th century, aren’t you? They’re not fragile…”

“…not fragile at all.”

“And the chairs!”

“No back support! I have to do stretches…”

Prof. Connell murmured to Jas. “Hey, you’re doing something technological with the library, Jas?”

“Yeah.”

“Fantastic. Now, this place needs to open up a little, you know? An amazing collection. Should be available to the best people, 24/7. No offence to these guys! Are you going to shake things up?”

Jas nodded weakly.

![]()

When he next saw Professor Connell, the Prof. was reading a book while sitting in the yew tree.

“Stop this at once.” Moira’s voice ricocheted off the walls of the quad.

“OK, OK. Tell me which part I can’t do. Is the tree the problem? Can I sit on the grass?”

Jas grinned, then un-grinned. Better not to appear partisan. Better not to be seen at all. He’d just arrived in the quad, and hung back.

“You’ve removed a book from the library. You signed a contract.”

“Yeah, I’m not sure that contract’s legal. Forgive me. Two months in a dark room could make anyone a little wild. Cabin fever. Jas?” He’d been spotted. “Take this book while I climb down?”

The Professor leaned down from the branches to pass Jas the book: a slim gum-bound paperback from the 1970s. Then the Professor dropped neatly onto the grass, and walked back into the library.

“Good morning, Jas.” Moira fell into step beside him. “You’ve done counter work, haven’t you?”

“Sorry?”

“You’ve worked on library counters.”

“Oh, yeah.”

“You’ve probably had moments like this.”

“Mm.” Students hiding books down their trousers. Tossing them in the air as they walked through the security sensor. “I reckoned it was their job to push it as far as they could, and my job to bat it back.”

“It’s not symmetrical, though, is it? If half the time the thieves win, and half the time we win, soon there’s no library.” Moira held the door. “Jas, I want all the books seeded. Not just the old ones.”

“Yes.” That doubled the project. Michelle would be delighted. “I mean — I’m studying, I start my course again in October.”

“What are your grades like? You could study here at St Simon’s, perhaps, and work in the Collection.”

The casual offer, in the chill of the dark room, sent a shiver up Jas’s neck. To go to University — to indulge in that old, expensive rite of passage. To use a real library, rather than downloading e-books.

Then there was the added appeal of starting in a new place. His friends, his mother, had been a life support. But to begin again, where people had always known him as Jas, was tempting.

Fred had been eavesdropping. “So, she said you could study here? Will you go for it?”

To distract him, Jas asked: “What are you researching?”

“The Gothic.” Fred widened his eyes, tossed his hair.

“Isn’t that old-fashioned?”

“It won’t die! It’s big in America right now. I’m working on getting myself a Stateside post-doc. Going to become a genius.”

“Can you — I mean, you can’t plan to be a genius.”

“You need more than brains. You need funding.”

![]()

Moira was clearly embracing technology, so Jas decided to give her another demonstration.

“University of Salisbury — special collections. My boss designed this for them.”

Moira prodded Jas’s device, bringing up related lecture notes, an audio clip of two students debating.

“You could have something like this,” Jas said. “Use work from the visiting researchers. Showcase what the library does.”

Moira shook her head without taking her eyes off the device.

“This modernity,” she said. Jas thought she was referring to something on the screen, until she continued: “This modernisation.”

“Yes?”

“It happens, of course, but it’s not inevitable. This project you’re leading. It’s incredibly useful. But it’s not the leading wave of an unavoidable rising tide.”

“Of course!” Jas tried to sound sympathetic. “Not every innovation suits every library.”

“I hope you don’t feel you’re here under false pretences.”

“No, no. I’m happy just tagging,” Jas lied. “I just — I liked this.” He pointed at the device, at the University of Salisbury’s shining showcase.

“I like it too.” Moira was faking regret. Dishonesty was contagious. “Perhaps if things were different.” Then, sincere again, she held out a Post-it note. “Here’s the number for St Simon’s admissions. I told them you’d be in touch.”

![]()

“…your fatuous little dictatorship…”

Professor Connell had been shouting for a couple of minutes. Jas’s hands had started to shake — he hated arguments — so he put down the seeding wand.

“What harm does it do anyone?” The professor was playing to the gallery, but getting no response. The madness expert shook her head regretfully, the occultist pursed his lips. “So that’s it? No second chance?”

“You used your second chance weeks ago, Professor,” replied Moira.

The professor scooped up his notebooks. Everyone found somewhere else to look as he stomped down the aisle, slammed the oak door behind him.

Jas scribbled on a piece of paper: What was that about? Pushed it towards Fred.

Fred mimed holding a box, squeezing: a camera. Except the Professor wouldn’t have made that gesture — he’d have taken his snap with a discrete tap on his phone.

Back to America, Fred wrote. Utterly expelled.

![]()

“So photographs aren’t allowed at all?” Later, in the pub, Jas was still keeping his voice down.

“Nothing’s allowed.” Fred pulled out a sheet of crumpled paper. “Here’s the contract researchers sign. Check which ones you’ve already broken.”

No stealing, no smoking. Fair enough. No photocopying, no scanning. Well, it might damage the books. But for every three reasonable requests, there was a big ask.

The researcher will not discuss the Harrad Collection in person or on social media.

Texts from the Collection will not be added to referencing apps or software including (but not limited to) Zotero, EndNote, RefMe…

Modernity isn’t inevitable, the librarian had said. She knew about social media and referencing software, but had decided to ban them. She wasn’t an aging dusty stereotype. She was well informed, and gatekeeping.

“I don’t like it either,” Fred said. “But I’m not going to climb a tree with a book up my arse to prove a point.”

“I don’t think anyone could expect you to do that.”

“I’m out of here, anyway.” Fred’s exodus predictions had taken on a personal, insulting note for Jas. This place that you want to get into? Fred seemed to be saying. I shun it. I’m better. I’m gone.

“So you said.”

“You should read up on the founder, Lady Harrad. She had some interesting principles.”

Lady Harrad had been born in 1890, Jas remembered vaguely. Victorian Values didn’t seem relevant here.

Jas felt Fred’s hand fumbling with his own under the pub table. He felt a flush of embarrassment, then realised Fred was trying to slip a tiny object into his palm.

“Have a look at that.”

“What—”

“There are more discreet ways to take photographs.”

Jas remembered the thick-rimmed glasses Fred wore for reading.

![]()

In his bedroom that evening, Jas phoned his boss.

“Jas! Great work so far.”

“Michelle, did I sign a contract to work here?”

“The company signed one.”

“Could you send me a copy? I want to make sure I’m sticking to it.”

“Sure. Probably common sense, though.”

But there was nothing common, or sensible, about the Harrad Collection.

Jas held Fred’s gift. The sliver of plastic was almost weightless. He knew he shouldn’t examine it. He’d lose his job, and any chance of studying here.

But a radical librarian had to be brave. Jas opened up Fred’s gift.

The memory card held a dozen files, all photos of pages. Jas read a header at random: ‘Unlike Other Women.’ Intrigued, Jas read on.

The woman was Unlike Other Women because she wasn’t a woman at all.

The page was from a transsexual autobiography. Jas knew the label was anachronistic, but the story felt so familiar. I rarely found myself drawn to feminine ways, and as a child threw myself into games with hoops and trains. The voice bubbled off the page. By the end of the first page, the narrator had become engaged but could not rest while betrothed to Daniel, having no wifely feelings for him. I then lived ten years in Clacton under the name of Donald.

‘Lived under the name of Donald’. What a world of activity that sentence glossed over. How had she — he — earned his keep, bought his clothes…

Jas checked the title of the book. Accounts from the Patients at Woburn Sands. Fred had also photographed the contents page, and there were twenty names: Constance, Jack, Alicia, Robert, JC. Were they all trans?

Published in 1878. A voice from history, a miracle.

![]()

Michelle, in Jas’s mind, said slow down, hold back. But Jas still cornered Moira the following morning for another demonstration. There were things in this collection too precious to stay boxed up. He’d known it objectively, but Fred’s illicit snaps — Donald’s story — had brought it home.

He needed to know where Moira stood.

Jas opened some images from the Lampeter website. “This was incredibly fragile, a Vulgate Bible from the 12th century.” Everyone liked illuminated manuscripts. “We scanned it without even opening it.”

Moira didn’t dismiss it out of hand. “How?”

“Michelle’s inventions.” He showed Moira pictures of the scanners. Sheets of graphene that slid in between pages, ultra-fast book flippers for the most robust texts, or ultrasound devices for the most fragile. “So now that book can never be lost, or destroyed, even if it’s stolen or water-damaged…”

“Or burnt.”

It felt wrong to mention fire, to a librarian. Like saying ‘Macbeth’ to an actor. “Yes.”

“Interesting.”

He would pitch hard, now, while he had her attention. “And with a collection like this, it seems such a waste for only the readers who are physically present to see it. I’m not saying you should throw it open…” He wanted that with all his untrained anarchist librarian heart, but he could haggle. “You would still absolutely be able to control exactly who has access to the texts.” She’d like that.

“So you see digitisation as a way to circulate the texts.”

It was such a basic question that it confused Jas completely. “Yes.” Of course, why else?

Moira sighed. “Jas, you are a very diligent young man. That’s why I hope you’ll work here for a long while, perhaps study here. But please understand, I will invest in any technology that means I know where my books are.” Tapping her desktop with a bloodless fingernail. “And which means they cannot be destroyed. Anything that makes it harder to steal them, to photograph them, to gain access to them without my knowledge — I want that.”

She wasn’t interested in opening the library up. She wanted to close it down. Maybe she’d misunderstood.

“We live in such an amazingly connected world, now,” Jas said. “It’s such a part of scholarship, and learning, and…” Vainly throwing keywords at the librarian.

“You’re right. In fact, I’ve been speaking to Michelle. She’s agreed that you can advise me on this.”

“Really?” A bloom of optimism.

“Building a security net, for a connected world. I’ll tell you about some of the worst offenders of the last five years.” Her eyes were bright at the thought of book thieves. Worse than that: library thieves. “You can tell me how you would have caught them.”

![]()

“Yeats,” said Jas. They were using famous writers for the game, today.

Each touch they give / love is nearer death… Jas had read that Yeats poem when he was learning about the librarian’s dilemma. It applied more to books than to lovers.

There were always two impulses in any librarian, any library, any collection: the desire to preserve a text, and the desire to make it available. Those two impulses were always at war. Each finger on a book lessened its lifespan.

But that was the marvellous thing about Jas’s scanning work: now the whole world could read a book without damaging it, without even touching it. How many other professions built around a central paradox could say: we solved it?

“Wallace Stevens. Hey. Sleepyhead. Stevens.”

Moira didn’t seem to be conflicted at all about her collection. Preservation trumped access, for her, every time. She was committing an act of enclosure: taking things which could easily be in the public domain and building a wall round them.

There was a dark side to collecting books. A hoarding, acquisitive desire. To keep the books away from other people and their sticky fingers. You had to temper that desire, and use your knowledge to increase the knowledge of others. Without that, you weren’t a librarian. You were just a hoarder.

“Stoker,” said Jas. “Bram Stoker.”

“Hey, not fair. That’s my turf. Anything Gothic — mine. Anyway. Ayn Rand.”

And now she wanted to put Jas’s diligent young brain to keeping people out. Poacher turned gamekeeper.

“You coming to the pub?”

“Already?” The whole day gone, and he hadn’t even tried to find the Woburn Sands book.

![]()

“All librarians are evil,” Fred announced, as they crossed the dark quad on the way home that night. “You want to be a librarian, Jas. It’s because they make a difference, right?”

Jas shrugged. There was still a light burning in the library. At lunchtime he’d emailed his best essays to an admissions tutor at St Simon’s, and he wouldn’t let Fred’s ramblings damage his chances.

Fred rolled on. “But librarians are supposed to be neutral, right? You want a book about raising Satan, the librarian’s supposed to give it to you. So how can you be moral and neutral? They want to make a difference, but they don’t say what difference they actually make.”

“But you gave me that book.”

Jas hadn’t intended to say it. He was tipsy. He wanted to check if he had someone on his side. “That made a difference, to me.”

“Oh, that was just queer solidarity. Hope you didn’t mind. I mean, I’m not assuming… Y’know.”

“I thought you were agreeing with me. Showing me something that should be shared — released.”

“Nah. None of that hippy stuff. Just a present.”

They climbed the stairs to Jas’s room, and at the door, Fred said: “Hold on a moment.” He reached behind Jas’s head, speaking and moving so casually that Jas thought Fred was brushing fluff off his coat collar.

Fred laid his hand across the nape of Jas’s neck and kissed him. His beer-tasting tongue parted Jas’s lips and moved in a slow circle inside Jas’s mouth. It was a bit much, but not unpleasant.

“Can I come in?” Fred asked.

“You’re drunk.”

“Have you met me? I’m always drunk.”

They were both laughing. He could feel the upwards curve of Fred’s lips, wished he could remember what Fred’s face looked like, if he’d been attracted to him at all before this ambush.

“Look, come in, but maybe not…”

“Not for that.”

“Maybe not.”

“But maybe.”

After all Fred’s threats to leave, his sudden attempt to move closer was sexy. Sexier than his musty suit jacket. “Perhaps.”

![]()

It was hard to plan the theft.

Jas found Woburn Sands the following day and read more of it in the library. It was too intense to read it in a dark public room during his lunch hour. It needed to be read on a windy beach, in a cafe in a city, on a bed, being charmed and buffeted by the voices from the past.

More importantly, it should be shared with the people who would be cheered by it, who were trying in the face of hostility to construct a history.

Jas checked the perimeter first: no door, no hatches. No means whereby he could slip the book into another bit of the building.

He argued with himself while he patrolled: I could get sacked.

I probably wouldn’t.

This would be a ridiculous way to remove all hope of studying at St Simon’s.

It’s really important. It’s the principle.

I’m a thief. When you steal from a library, you steal from everyone in the world.

That’s such a pre-digital idea. A childish idea. I’m not a thief. I’ll bring it back.

You’ll keep it.

Shut up.

Jas looked at the windows. In most libraries, the windows were sealed. If you didn’t have a central courtyard, you were condemned to swelter. Here, at least, they were open.

Jas set his book on a wide windowsill.

Then he worked for another half hour, to make it less suspicious.

“I’m going for lunch.”

“Mind if I join you?” said Fred.

“Oh, I need to do some things.”

Fred’s poker-face rebuked Jas. It would be tactless, after last night, to fob him off.

“Sorry. We could meet later?”

Fred shrugged, all bony shoulders and nonchalance. “If you like.”

Jas forced a smile. His footsteps down the library aisle had never sounded louder.

Moira was in her office. His heart slapped insistently, something is wrong, something is wrong.

Jas opened the library door, turned hard right along the wall, to the window where, on the sill, his prize waited for him. He scooped it up silently, slipped it into his bag and kept walking.

In his room, Jas slid the book under his mattress. No, that was the first place people would look.

He turned round and round, eyeing every crevice and seeing no hiding place. What had he done? A sackable offence, definitely a sackable offence.

Better to scan it, and take it back straight away. He popped the book into one of the slower flicker-scanners and watched it deftly turn the pages.

The door opened.

Jas tried to stand in front of the device.

Fred stood in the doorway.

“Cheeky,” he observed. “Oh, no, don’t faint on me…”

Jas sat on the edge of the bed and waited for the room to stop spinning.

“It’s not enough,” Jas said, when he was calmer. “I mean, it’s not fair for me just to borrow a book that I want to read. There must be other books, useful to other people…”

“Aye.”

“What should I do?”

“Well, what can you do? You can’t take snapshots of everything.”

“I’ve got these scanners. Really good scanners.”

Fred raised his eyebrows. “Moira wouldn’t like that.”

“Do you think we could talk to the Vice Chancellor of the University?”

“‘We’? Leave me out of it.”

![]()

For the next fortnight, Jas was remarkably productive in both halves of his double life.

He set up the online security net Moira had requested. First, he cross-referenced the Harrad Collection catalogue against other library catalogues to find the really unusual books. Then he set up alerts, triggered if anyone mentioned one of these rare books online.

“That’ll catch them,” Moira said. It was the most satisfied he’d ever heard her.

After work, Jas smuggled texts out of the library. Ones that seemed to him to relate to queer history, a couple every day. He scanned them and returned them, too nervous even to read them. They went no further; he couldn’t work out how to share them. It was a futile, miniscule act of rebellion.

Most evenings he ate dinner in the pub while Fred drank, and they slept in Fred’s room together. And while Jas worked and stole and slept, he waited for an offer from St Simon’s.

![]()

He woke up in Fred’s room, colder than usual. Fred’s warm weight was absent.

Jas wondered if he should go back to his own bed. It was weird to be here on his own. The pillows smelled of cigarette smoke — it had seemed exotic and sexy as he’d fallen asleep, but now he didn’t want to rest his face in it.

Jas walked as softly as he could to his own room.

There was a light shining under the closed door. He flung open the door, hoping to startle whoever was in there.

The surprises came in quick waves.

To find Fred in his room, when he’d just come from Fred’s bed.

To see Fred juggling very competently one of the graphene scanners, clearly having used the slippery and delicate thing before. A flicker-scanner fanned a stack of five books in one corner of the room, and the ultrasound machine hummed in another.

But mainly, Jas was startled by the scale of it. There had to be a hundred books stacked on the carpet. Fred alone had clearly carried them from the library, intending to scan and replace them tonight. Up and down the stairs, and no lifts. Fred was enthusiastic, manic at times, but Jas had never seen him so industrious.

Jas realised that Fred and Moira both scared him. But at least he knew what Moira wanted.

Fred sprung towards him. Wrapped his pyjama-clad arms round him.

“You were right. Information wants to be free,” said Fred.

“Fred, why…” Fred had been awake for hours, Jas for only minutes. He couldn’t think straight, and Fred talked over him.

“You’ve opened my eyes,” said Fred.

“You’ve nicked my scanners.”

“Borrowed. Just for tonight. But something’s better than nothing, eh? Send a few books out into the world, like doves after the flood.” Fred tightened his hold.

Jas spoke into Fred’s mop of smoky hair. “You need to promise — swear — you’ll never do this again.”

“OK, OK.”

“Have you shared any of it?”

“No.”

“You have to wipe your memory cards, wipe everything. I’ll help you put the books back.”

Up and down the stairs in the dark. Barefoot on stone, so as to make as little noise as possible, so that each step was painful — like the little mermaid, he thought, as sleeplessness sent his brain off on strange tangents.

He was so bone-cold and bone-weary at the end of it that he never wanted to see Fred again. But so much of both that he let him creep into his bed and hold him.

“Promise. Never again.” Jas knew his own lesser transgressions would have to end, too. Even though they was hardly comparable to Fred’s efforts. No more scanning for either of them.

“I promise,” said Fred.

![]()

An alert was triggered the next morning; something caught in the new security net. An academic in America boasting about working on a ‘lost’ Gothic novel. It could be a coincidence. Jas didn’t report it to Moira.

Fred didn’t turn up to work. Catching up on sleep, Jas guessed.

An email at midday from St Simon’s made Jas an offer: a place on an undergraduate degree, starting that Autumn.

Jas prayed they’d never find out about the scanned books.

During the afternoon, a different fear crept over him. If he took up the offer, would he be tied to Moira and the library indefinitely?

![]()

As Jas was leaving the library, that evening, Moira spoke. “Wait, Jas.”

She’d found out. About the alert Jas hadn’t reported, or his thefts, or Fred’s misdeeds. She was going to sack him, prosecute him, have him barred for life from all libraries.

Or she knew about his offer, and he was trapped.

“I’ve not been fair to you. Come with me.”

Moira led Jas a long way into the library. Unlocked doors, revealed a dusty room. On a table lay metal guillotines, a pin-cushion stuck with three-inch needles. Moira was going to torture him. No, don’t be daft.

“I do some small repairs, here. Have a seat.”

She laid a book in front of him. Published in the 1940s, maroon cloth binding. He picked it up, automatically looking for the crevice in which to insert the tracking seed.

“The founder of the Collection.”

Jas shifted his attention from the binding to the content. A Life of Lady Harrad. The contents page described the founder campaigning for women’s suffrage; then for pacifism and the League of Nations; then against fascism, and in favour of self-government for India. An all-round good egg, Jas thought.

“Lady Harrad saw the book burnings in Berlin. Including the archives of the Hirschfeld institute.” Did Moira know that Hirschfeld would strike a chord with him? Did everyone know he was queer? “She started the Collection after that.”

Surely, then, she’d want the world to use the damn Collection. Not for it to sit and moulder in a stone room in an odd corner of a small country. He phrased it as mildly as he knew how. “So she knew it was important to — preserve ideas.”

“She collected books to get them out of circulation.”

Jas stared in disbelief at the frontispiece photograph of an Edwardian teenager, big eyes and swept-up hair.

“Anti-suffragette materials, fascist tracts,” said Moira. “She boxed them up and sent them home to her mother and kept collecting.”

Moira laid other books on the desk. Jas opened the covers carefully.

The Segregated City.

Motherhood in the Lower Classes.

Disordered Desire: Deportation as Solution.

“And the Collection kept collecting, after she died.”

More volumes were added to the desk, modern ones. Virology, Anthropology, Economics.

It was horrible because the books wore all the trappings of legitimacy: smart fonts, cloth-bound covers, a familiar formal layout. Like a polite voice saying terrible things. And because Jas loved books, totally bloody loved books — it was like the voice of a friend in a nightmare.

Were all the texts in the Collection similarly awful? Had he been surrounded by walls crawling with malice, for weeks? But the book Jas had found, the book from Woburn Sands — had Lady Harrad disapproved of it? Why was it here?

“There are good things, too.”

“I don’t doubt it. She didn’t have time to read everything herself. And fashions change, in politics, as in everything.”

Jas took deep breaths, looked away from the books. “So why keep them all?” he asked.

“For the same reason that we preserve the smallpox virus. They could be useful to study. That’s why we permit researchers to visit. But the books shouldn’t be allowed to spread.”

Jas’s head was swimming with objections. Paternalistic. Patronising.

“I suggest you take tomorrow,” Moira offered, “To look around. Read the books. Talk to the researchers. Ask them about their work: the unethical medical experiments — the economists advocating enforced labour — the novels that are as beautiful as Proust but, oh, five times as anti-Semitic. See if they think those books should be available to the world.”

She was defending herself heatedly against objections Jas hadn’t even raised. “OK. I will.” He needed the conversation to stop.

Moira sighed. “It’s expensive to keep people out. Distance is a great boon. That’s why Lady Harrad lodged the Collection at St Simon’s. It’s rather far from everywhere.”

![]()

Jas walked on the beach for an hour to get his head straight. He imagined the horrors of the Collection, and tried to reconcile that with the dark, orderly library room. He heard the shingle growl as the waves dragged it back, then saw the surf roil and crash.

When he was exhausted, he turned back towards the University. Across the beautiful quad, which his new knowledge still couldn’t make ugly. Up the stone stair, opening the door to his room.

The sight was so much as it had been last night that Jas wondered if he’d become stuck in a loop of time. Fred, cross-legged on the bed, feeding books into scanners. More books, if anything, than before.

“Ah! Finally! You’re back.” Fred sprung up and moved from device to device, clicking out memory cards.

“You promised…”

“I lied.”

“You’ve been here all day?”

“Yep.”

“But you were up all night, as well. You can’t have slept…”

“I’ve hardly slept for two weeks, Jas. I’ve been in here every night. I’m on uppers. Didn’t you bloody notice?”

“What are you doing?” He definitely wasn’t releasing books like doves after the flood.

“I’m taking everything relevant from the Collection and I’m going to America. Where

I’m starting a post-doc. I’m not smart enough to get it on my own. No, no, Jas — I know my limits. I have to research a unique resource. And I have to bring that resource with me.” Fred tucked the memory cards into his breast pocket. “Nobody’s even heard of half these texts. They’re nasty stuff. Turn your hair white.”

“This is all for your research?”

“Of course. Oh, and because information, it wants to be free, apparently.”

“You set off the alarm I set up.”

“One of my future colleagues. Got overexcited about one particular book. Idiot.”

Jas tried to breathe evenly. He should tell Moira. But it was his own bedroom stacked with books, his own equipment (smuggled into the building) which had pirated them.

“Anyway, I’m off tomorrow,” Fred announced. “But first: the final step.”

“What?”

Fred’s eyes sparkled.

“I burn the originals.” Fred reached into his inside pocket.

Jas had a sudden vision of the room on fire, bindings blazing, leaded windows cracking in the heat.

Jas hit Fred.

He’d never done it before, and he did it badly. His knuckles jarred against Fred’s cheek, instantly aching like they were broken. But at least he’d stopped Fred reaching for a lighter, or a bottle of petrol.

Fred reeled back, clutching his face. Laughing. “Good God, Jas, I’m not going to do that! Why would I need to do that? You’re so bloody gullible!”

The side of his face was red, a spreading blotch, horrifying Jas.

“I wouldn’t burn them. They’re too bloody valuable. I mean, I’ve sold a lot of them. To cover my relocation costs. You wouldn’t believe how much a neo-Nazi will pay for a—”

Jas hit him again. No ticking clock as an excuse, this time.

Fred fell, and lay on the floor, gulping.

“Sorry,” said Jas automatically.

“Help me up, then.”

Jas couldn’t move. He could have helped skinny, frenetic Fred, the friend who was reaching up a hand to him. But Fred had metamorphosed himself into something untouchable. Revulsion welled up in Jas so strongly that it became awe.

The man at his feet was a library-thief. He had stolen from everyone in the world.

![]()

Unlikely Story

Unlikely Story